The U.S. general likely to become the country’s top military officer recently called Russia the “greatest threat” to America, and a new U.S. military doctrine includes it on a list of global bad actors. But the government remains divided on how to respond to Moscow’s increasingly provocative behavior, writes Donald Jensen, resident fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations.

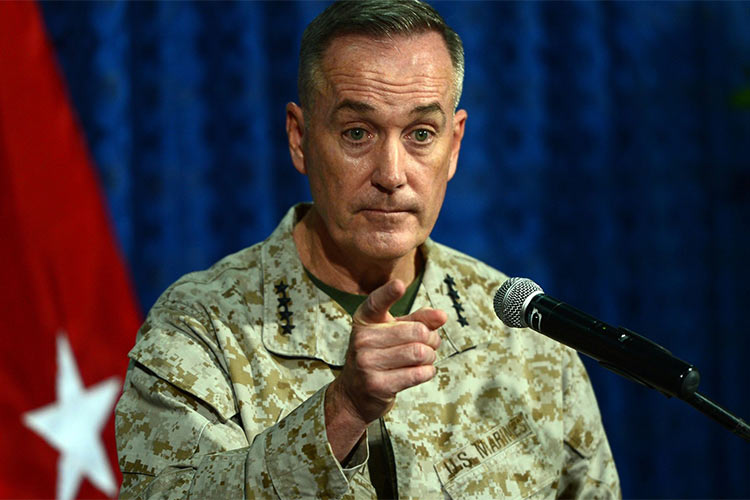

According to General Joseph Dunford, the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s nominee, Russia is an existential threat to U.S. national security. Photo: AFP

On July 1, the Pentagon released a new U.S. National Military Strategy (NMS), the first update to the document since 2011, in which it warned that the threat of a major war between the United States and another nation is growing. The update reflects the new international security situation, one in which the U.S. faces challenges from state adversaries such as Russia, Iran, and North Korea—which the report calls "aggressive threats to global peace“—while simultaneously having to confront militant groups such as Islamic State. (The report also singles out China as a “regional competitor,” but says the administration of U.S. President Barack Obama wants to “support China’s rise and encourage it to be a partner for greater international security.”) Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Martin Dempsey wrote in the introduction that over the last four years, “global disorder has significantly increased while some of our comparative military advantage has begun to erode.” It also noted that the United States is no longer guaranteed to have technological superiority over its adversaries.

The new report’s language about the Russian threat is a clear demonstration of how significantly the Obama administration has shifted its mindset since the era of its ill-fated “reset” policy with Moscow. In 2011, at the height of that policy, the previous NMS pledged to “increase dialogue and military-to-military relations with Russia, building on our successful efforts in strategic arms reduction.” That 2011 document also welcomed Russia “playing a more active role in preserving security and stability in Asia.” The new document has a drastically different tone about the growing threat from Moscow—and yet the White House still appears to be ambivalent about how to deal with Russia.

On the one hand, General Joseph Dunford, the Obama administration’s nominee to be the new chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on July 9 that Russia is an existential threat to U.S. national security. Its behavior toward its neighbors, the general said, “is nothing short of alarming.” He also said it was “reasonable” to send Ukraine heavy weapons to defend itself against Russian aggression. The day before, U.S. Air Force Secretary Deborah James said upon returning from a series of meetings in Europe with U.S. allies: “This is no time to in any way signal a lack of resolve in the face of Russian actions.”

As is so often the case, the diplomatic corps has struck a less hawkish tone than the military brass. U.S. State Department spokesman Mark Toner said on July 10 that Secretary of State John Kerry disagreed with Dunford’s assessment of Russia as an existential threat, although he added that U.S. officials have been “very frank” with Moscow on areas of disagreement, including its involvement in Ukraine. Obama administration officials have often pointed out that the White House and the Kremlin still cooperate on certain international issues, including the Iran nuclear talks and the civil war in Syria. President Obama has refused to provide arms to Kiev, despite the fact that Congress has explicitly granted him the authority to do so and Defense Secretary Ashton Carter supports the move.

Indeed, despite the new rhetoric in the NMS about Russia’s global ambitions, the Obama administration has acted as though the Ukraine crisis is primarily a threat to regional stability in Europe, rather than to the international order—an order that the Kremlin openly says it wants to overturn. At times, it has seemed as though the U.S. considers the Ukraine war a distraction from the ISIS threat, the Greek economic meltdown, and the negotiations on a nuclear deal with Iran. Washington has thus farmed out the diplomatic leadership in the campaign to counter Russia to the European Union, and especially to Germany. The U.S. has adopted a strategy of strengthening NATO’s eastern flank in an attempt to reconcile several contradictory policy threads: reassuring its European allies; continuing to rebalance its international priorities and building up its position in East Asia; and avoiding unnecessarily escalating tensions with Russia (demonstrated by Washington’s cautious support for Ukraine). The West’s sanctions policy also has been selective and incremental.

The military doctrines of both sides are products of each country’s national security politics and elite perceptions, as opposed to accurate descriptions of the international security environment or frank portrayals of U.S. and Russian strategy for coping with threats.

The U.S. is understandably eager to avoid an unnecessary escalation of military hostilities in Ukraine and wants to reach a calibrated and proportionate response to Moscow’s aggression. But it is doubtful that pulling punches on Ukraine increases the chances of making progress on other issues. The Kremlin will “help” on Syria or Iran or ISIS (If that is what Russian involvement can be called) only if Moscow calculates that such involvement advances Russia’s national interests.

The reaction to the new U.S. doctrine by Russian officials and commentators was more or less unified, in contrast to the divisions among U.S. officials. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov attacked the new U.S. strategy as “confrontational,” saying it would not help improve relations already strained by the crisis in Ukraine. He also said a new version of Russia’s national security strategy, currently being drafted by the government, would provide for countermeasures against all threats. Sergei Rogov, director of the Institute of the U.S.A. and Canada at the Russian Academy of Sciences, said the U.S. document provided doctrinal support for a new American “cold war” against Russia. Another observer wondered how the U.S. could carry out its commitment to working with international coalitions and at the same time reserve the right to act independently, “including with the use of force.”

Russian observers made little mention of the fact that Russia published an assertive new military doctrine of its own at the end of 2014, a revision of the previous version from four years earlier. In its 2014 doctrine, Moscow said it viewed the prospect of a large-scale war involving Russia as slim, but said the overall security environment had deteriorated and noted a more immediate threat from NATO. Also new was a reference to unnamed actors using information warfare and political subversion, weapons that it implied were meant to threaten Russia. (The document, of course, did not mention Moscow’s own extensive use of these tactics).

The military doctrines of both sides, therefore, are products of each country’s national security politics and elite perceptions, as opposed to accurate descriptions of the international security environment or frank portrayals of U.S. and Russian strategy for coping with threats. After more than a year of Russian meddling in Ukraine, the West is still trying to figure out Russia’s objectives. Moscow, in turn, proclaims dogma that not only misreads its adversaries but projects onto the West its own insecurities. (In a recent interview with Kommersant, Russian Security Council chief Nikolai Patrushev claimed fantastically that the U.S. and Europe “would like very much to see Russia cease to exist as a country.”) With the standoff over Ukraine and the global order far from resolved, it will be interesting to see how subsequent revisions evolve. Unfortunately, we should have little confidence that they will be more adept at grasping reality.