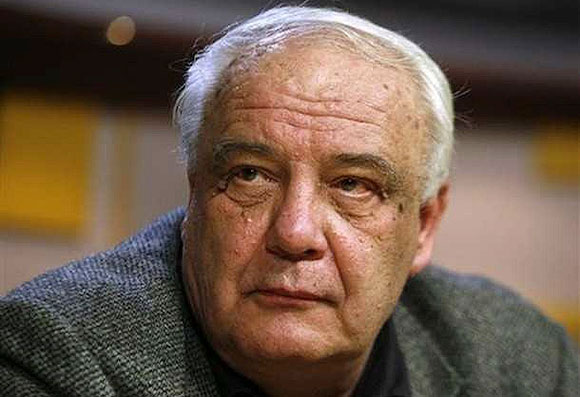

This spring, Russia will see a new wave of protests, which could lead to a change in government and to the collapse of the current political system. Such is the view of Russian writer Vladimir Bukovsky, a legendary Soviet-era dissident and a leader of the opposition “Solidarity” movement, who spoke with IMR’s Olga Khvostunova.

Olga Khvostunova (O.Kh.): Russia has recently adopted a new law that bans American citizens from adopting Russian orphans. This law has been met with severe criticism. How do you view this initiative?

Vladimir Bukovsky (V.B.): This decision came as a surprise to me, mostly because the legislation makes no sense at all. It is a so-called “asymmetrical response” to the Magnitsky Act, but this law, in fact, has nothing to do with the Magnitsky Act. The Russian authorities decided that they had to punish the U.S. somehow, and took this schizophrenic decision. There is a good saying in England: “cut off the nose to spite the face.” This is pretty much what the Russian legislators did, and they only made it worse for themselves.

O.Kh.: Their reasoning is that the Magnitsky Act targets Russia and humiliates it.

V.B.: This is something I cannot grasp. The Magnitsky Act does not target Russia—it targets corrupt officials, whom the Russian authorities – beginning with the president – promised to fight. They should welcome the Magnitsky Act. It would be much worse were the West to refuse to reveal the names of these officials and freeze their assets, so that they could continue to hide their money abroad. The Russian Duma should write a thank you letter to the U.S. Congress for passing this Act. Instead, Russian deputies come up with some sort of “asymmetrical response.” Following the same logic, they could have banned cacti on Russian territory. I increasingly feel that the majority of Russia’s political establishment consists of mentally ill people.

O.Kh.: Did you expect other restrictive measures that were also adopted, such as the laws on increased penalties during street protests, on libel and on treason?

V.B.: Repression, tightening of the screws, restrictive legislation – all this was expected. During the mass protests, intentional provocations were organized to create grounds for more rigorous regulations of the rallies. Take the new law on treason, for example – it is very inexpert. I think that any decision under this law will be overturned by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, because the definition of “treason” is broadened to a point where any conversation with a foreigner can be qualified as treason. I do not understand why people fail to learn from history. In the Soviet system they could send a person to jail for talking to a foreigner. Did it help the Communist Party stay in power?

“We are talking about three to five years, during which the system will undergo a radical and rapid collapse.”

O.Kh.: Many experts say that these laws make Russia’s political system similar to the Soviet model. Do you think that the Soviet Union can be recreated today?

V.B.: It is impossible to recreate a system that would be as rigid as the Soviet one. Only a pale imitation can be created. Russia is an open country, people can come and go, they have open access to information. This cannot be banned, and hence it is impossible to impose a system of spy mania and total control. Russia cannot go back to the Soviet past. So why even try? They can pass other restrictive laws that will destroy another few hundred lives. But it makes no sense in the end.

O.Kh.: Perhaps Russian legislators do not care about the country, but only about their own security and their own money?

V.B.: It is true that they do not care about the country, but they will not be able to provide security for themselves by such laws. It is naive to think that they can protect themselves with such crude police methods. The Communist Party was unable to do so, despite having much more brutal methods at its disposal.

O.Kh.: Still, the Soviet Union lasted for more than 70 years.

V.B.: True, but after the Soviet experience Russia will go through this period much faster. People still have memories of the USSR, and they do not need someone to explain the situation to them again. They have no more trust for the current authorities.

O.Kh.: In your opinion, how long will it take to demolish the current political system in Russia?

V.B.: The current leadership of Russia could be changed at any time, even this year. The political establishment may want a leadership change to renew Russia’s image. The current system is unfavorable to them, because it stalls investment flows and hinders business opportunities. But changing the leader does not mean changing the system, and it will not mean much. However, the collapse of the system could happen quite soon, for one thing, because of the drop in oil and gas prices. Besides, everyone nowadays is talking about shale gas, and Europe happens to have huge reserves of it. Gazprom may soon lose its status of Russia’s economic flagship. The almost monopolistic position of Russia as a main gas exporter to the European market will come to an end. It is difficult to predict the exact time, because much will depend on the global environment.

O.Kh.: Can you give an approximate timeframe?

V.B.: Oil and gas analysts say that by 2020, Russia will be completely irrelevant as a supplier for Europe. Naturally, the people in the Kremlin know about this. They understand that something must be done. Hence, internal conflicts and power struggles may break out within the regime. I think that we are talking about three to five years, during which the system will undergo a radical and rapid collapse.

O.Kh.: One view is that the recent toughening of the system is linked to Putin personally, and that if a compromise figure like Dmitri Medvedev were to come to power, he would let off steam and postpone the collapse of the system. Do you agree with this?

V.B.: I think it is the opposite. Let us remember Gorbachev’s “perestroika”, which accelerated the collapse of the Soviet system. In the 1960s and 1970s, when we were calculating when the USSR would break up, everyone agreed that it would happen by the end of the 20th century, but it happened 10 years earlier. Gorbachev started repairing the system, but it turned out that what he did was not enough for the economy, but too much in terms of losing control. Political control was lost, while the economy failed. I think that if the current authorities launch liberal reforms, the collapse of the system will accelerate.

O.Kh.: So Putin was right in his calculations: he tightened his control to prevent the collapse of the system?

V.B.: Yes, but it is a short-sighted approach. This way, he will only gain two or three years, no more.

“By the spring, the public will wake up again, and will begin to express its dissatisfaction. But it will be a different public, which will not be easy to deal with.”

O.Kh.: What role can the opposition movement play in this process? Last winter’s protest wave was a surprise for many, including for the authorities. Can something similar happen today?

V.B.: The protests that happened a year ago were indeed unexpected. It was clear that the public had become dissatisfied, but it was impossible to predict when this dissatisfaction would break through. But as soon as the first sociological surveys of the protests came out, it became clear that this was a movement of the intelligentsia, and the intelligentsia would not opt for a head-on conflict with the regime. So the authorities had the option of blocking this movement with tough measures – this is what we are seeing today. The protest movement is a positive development, but, unfortunately, it cannot change the regime.

O.Kh.: So who or what can change the regime?

V.B.: There will be a second protest wave. The intelligentsia does not want to fight the police, so the intelligentsia will be replaced by a simpler, hoodlum-type public – there are many people like that in Russia. They enjoy clashing with the police. And this thousands-strong crowd armed with shanks will go against the unlucky riot police.

According to Vladimir Bukovsky, the second wave of anti-government protests in Russia will be very different from the “intelligentsia” rallies of 2011-2012.

O.Kh.: When can we expect this second wave?

V.B.: I think, this spring. It is winter now, and that plays against the people. During the crisis with Solidarity in Poland, there was a popular saying that “winter belongs to the government, and spring belongs to the people.” The Russian authorities are now going after the people they consider to be opposition leaders, and are toughening repressions. But by the spring, the public will wake up again, and will begin to express its dissatisfaction. But it will be a different public, which will not be easy to deal with.

O.Kh.: Do you think that the Coordinating Council of the Opposition can help?

V.B.: I think that the Coordinating Council is a big mistake of the opposition. It is a pointless waste of time and efforts. An organization with 45 members cannot function and make decisions. Even if every member of the Council is given only five minutes to speak, it will take about four hours in total. No one ever creates organizations that need to make decisions with more than 10-15 members. Besides, the Coordinating Council has a broad representation of different political views, which brings even more disagreements. On the top of that, the authorities will try to split the Council. There are two distinct forces within the Council—liberals and conservatives. By giving preferences to one group and repressing the other, the regime can turn them against each other. It will not be hard to do, considering the Council’s mixed composition.

O.Kh.: Nevertheless, some people view the Council positively in terms of the experience of civic participation in fair elections. The mere fact that some 100,000 people took part in the election says a lot.

V.B.: These 100,000 people took part in the election hoping that it would make a difference. But what comes next is disappointment. They elected this Council, but it is incapable of making decisions. The very idea of this project was fraught with defeat. Things like that should not be done.

“It is wrong to focus only on Moscow and St. Petersburg. Today, Russia’s regions are more active than ever – and they can make a significant contribution to the protest movement.”

O.Kh.: What should be done then?

V.B.: Peripheral and horizontal links should be developed, as should regional movements. It is wrong to focus only on Moscow and St. Petersburg. Today, Russia’s regions are more active than ever – and they can make a significant contribution to the protest movement. Russia is a huge country, and if there is unrest in the regions, the central authorities can do nothing about it. They lack resources to suppress such unrest. It is pointless and expensive to redeploy special police forces from Moscow to the Far East, for example.

O.Kh.: But revolutions usually take place in capital cities. Do you think that regional protests can result in the change of the federal government?

V.B.: Let us recall the late 1980s and early 1990s, when miners were on strike all over the country. In this contest, the emergence of the Interregional Group of Deputies [the pro-democracy group in the Soviet parliament] and its political activities were a serious factor. Without the unrest in the regions, however, this group would have been seen differently: a hundred intellectuals gathered in Moscow, so what? The revolution will, of course, take place in the capital. But with unrest in the provinces, any protest in Moscow will make the situation hopeless for the regime.