2014 was full of dramatic developments and unexpected turn of events. Some of them, such as the annexation of Crimea and Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine, were hard to predict. Others, like Western sanctions, Russia’s expulsion from the G8, and the economic recession, had been ripening for a long time. Here, IMR recounts this year’s key events, month by month.

Crimea joining Russia can be called the most memorable event of 2014. However, while the majority of Russians view this event in a positive light, the rest of the worlde recognizes it as an act of aggression. Photo: Dan Kitwood / Getty Images

January: Euromaidan

Photo: Konstantin Chernichkin / Reuters

Mass protests in Kiev’s Maidan started on November 21, 2013, as a reaction to the Ukrainian government’s refusal to sign an economic association agreement with the European Union. The decision was made shortly after Viktor Yanukovich, then—Ukrainian president, visited Moscow and discussed this issue with the Kremlin. Meanwhile, Moscow continued its historic opposition to pro-European movement in Kiev. However, the Kremlin underestimated the resolve of the Ukrainian people. In January 2014, the Ukrainian Rada passed a number of amendments that restricted protest movements and the media in Ukraine, thus violating individuals’ fundamental rights and freedoms. Following a month-long confrontation between pro-European demonstrators and the Ukrainian government in the Maidan, the crisis reached a tipping point. For the rest of January, Kiev was shaken by furious street fights and clashes between Maidan demonstrators and the police. By the end of the month, the amendments had been repealed.

In the meantime, on January 17, the Russian State Duma passed legislation that restored the “against all” ballot option in elections for positions at all levels of government except the presidency. That option had previously been abolished in 2006.

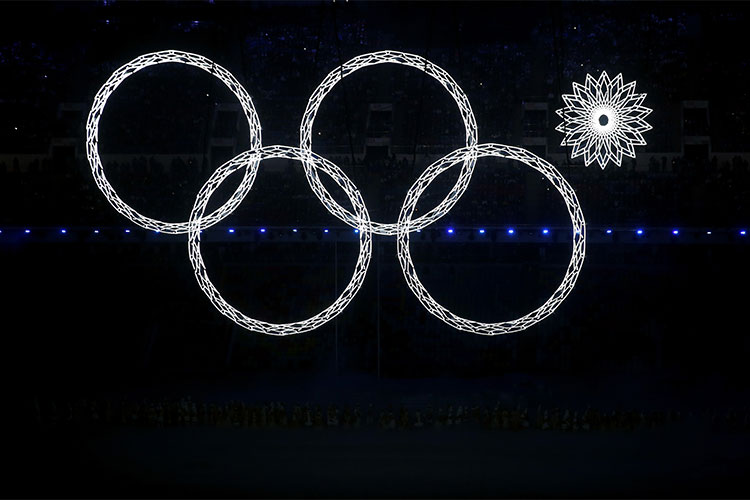

February: Sochi Olympics and the Kiev Revolution

Photo: Bruce Bennett / Getty Images

Between February 7 and 23, the southern Russian city of Sochi hosted the twenty-second Olympic Games. The total cost of the event was estimated at a whopping $50 billion—the most expensive Games in history. The Russian government’s staggeringly corrupt practices and violations of human rights in the days leading up to the Games were widely broadcast by the global media. IMR created an interactive online guide to the most major of these violations and abuses. Russia nevertheless won the Olympics in terms of overall medal standings, which Putin interpreted as a personal triumph.

Even though the Olympics made global headlines that month, the ongoing crisis in Ukraine ultimately ruined Putin’s jubilant mood. On February 21, after mediation from various foreign ministers of EU countries, Yanukovych and Ukrainian opposition leaders signed a deal to try to end the political crisis in the country. However, Maidan protesters rejected the deal and demanded that Yanukovich resign. That same day, the Rada proposed that Yanukovich be impeached. Overnight, Maidan protestors managed to seize control of Kiev’s key administrative buildings. Yanykovych fled. On February 23, Alexander Turchinov was appointed acting president. On February 27, a new government was formed.

While the revolution unfolded in Kiev, a guilty verdict was handed down to eight prisoners of the Bolotnaya Square Case on February 21 at Moscow’s Zamoskvoretsky court—a decision that received hardly any attention from the Russian media. All of these individuals have been recognized as political prisoners by the Memorial Human Rights Center.

March: Annexation of Crimea

Photo: Thomas Peter / Reuters

In the wake of the Ukrainian crisis, on March 1, Russia’s Council Federation approved Putin’s request to deploy the Russian military into the territory of Ukraine until resolution of the social and political unrest. Subsequently, a group of unidentified armed men wearing unmarked uniforms took over the Crimean peninsula and occupied its administrative and other strategic buildings. Later on, these men were nicknamed the “little green men” and “polite men.” The Kremlin refused to admit that the troops were Russian special forces.

A referendum on the status of Crimea was held on March 16. The Russian government claimed that 96.7% of Crimeans voted in favor of secession from Ukraine and reunification with Russia. The United Nations’ General Assembly approved a resolution declaring the referendum invalid. On March 18, however, the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol officially became part of Russia—an event that Putin labeled the “restoration of historic justice.” The international community, however, deemed the event a violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and refused to recognize the Russian Federation’s annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol. While the “Crimean campaign” boosted the Russian president’s approval rating among Russians to 82%, the G8 voted to expel Russia from its ranks, and the United States, Canada, Australia, the European Union, and New Zealand imposed the first round of sanctions on Russia.

On March 31, Deputy Andrei Lugovoy, a member of the Liberal Democratic Party, introduced a bill to the State Duma making the failure to provide information about foreign citizenship (nationality) to immigration authorities a criminally liable offense. The penalty fee was set at 200,000 rubles.

April: The Kremlin’s Reaction

Photo: Maxim Stulov / Vedomosti

An abrupt cooling down of relations between Russia and the West in the aftermath of the Crimean annexation forced the Kremlin to go on the defensive. In Russia, the authorities announced a new series of repressive measures against the opposition and civil activists.

On April 23, the State Duma passed a law on liability for the public rehabilitation of Nazism. Some parts of the new law repeat verbatim Article 190-1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, under which many Soviet dissidents were convicted for “spreading knowingly false fabrications” about the Soviet system. A few days later, on April 29, Russia’s Federation Council passed a bill tightening government control over the dissemination of information on the Internet and grouping bloggers together with journalists.

May: The New Ukraine

Photo: Reuters

Meanwhile, the situation in Ukraine became a smoldering conflict. Putin claimed that in the 1920s, eastern Ukraine was part of Novorossiya, not part of Ukraine proper, thereby giving separatists in the Donetsk, Luhansk, and Kharkov regions a green light. In response, the Ukrainian authorities instigated antiterrorist operations.

On May 11, two status referenda were held in Donetsk and Luhansk. The majority of these regions’ residents voted in favor of the creation of “people’s republics” and secession from Ukraine. The referenda were accompanied by numerous violations, as well as clashes between the Ukrainian security forces and separatists. On May 24, the two separatist republics signed an agreement confirming their merger into a confederation called Novorossiya. The international community refused to recognize the referenda results.

On May 25, Ukraine held presidential elections. Ukrainian businessman and former confectionary tycoon Petro Poroshenko got 54.71% of the votes and became the new president.

June: Isolation from the West and the “Chinese Turn”

Photo: Reuters

The annexation of Crimea dramatically affected Russia’s image globally, a shift that was particularly noticeable at the celebration of the seventieth anniversary of D-Day in Normandy, which coincided with the G7 summit in Brussels. For the first time since 1997, world leaders met as the G7 rather than as the G8, following the expulsion of Russia from the group as a result of its invasion of Crimea.

The Ukrainian crisis, the subsequent sanctions, and Russia’s increasing isolation from the West forced the Kremlin to seek a market alternative to Europe among more sympathetic regimes in Eurasia. Shortly before the G7 convened in Brussels, Russia’s Gazprom and China’s CNCP signed a thirty-year contract to supply Russian gas to China at a discount price. The $400 billion gas deal required China to make a $25 billion advance payment to Gazprom to start the construction of a pipeline from Russia toward the Pacific named the “Power of Siberia.”

On June 30, Putin signed a law directed at toughening Russia’s laws on fighting extremism. Its provisions include imprisonment of individuals who fund extremist activities or call for extremism via the Internet.

July: MH-17 Catastrophe

Photo: Reuters

All summer fierce battles between the Ukraine National Guard and separatists were tearing apart the eastern and southern parts of Ukraine. Although Putin continuously refused to acknowledge the presence of Russian troops in Ukraine (however, he would admit they could be volunteers from Russia), many journalists and independent observers collected abundant documented evidence to prove the opposite.

The downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine on July 17 became the culmination point of the Ukrainian conflict. A total of 298 passengers, the majority of whom were Dutch citizens, died in the crash. The commission established to investigate the incident still has not found out whether pro-Russian rebels or the Ukrainian military was responsible for shooting the fatal missile. Western governments believe that the plane was shot down by pro-Russian separatists using a Buk-M1 surface-to-air missile.

Fearing a spillover of separatist sentiments from Ukraine to Russia, Putin signed a law toughening punishments for calls for separatism.

August: “Sanction Wars”

Photo: TASS

In late July, Russia’s aggression in eastern Ukraine triggered tougher sanctions by the United States and the European Union. The sanctions targeted certain key sectors of the Russian economy that are closely connected to the ruling elite, including energy, defense, and finance.

On August 7, in retaliation for Western sanctions, Russia banned food imports from the United States, Canada, the European Union, Australia, and Norway for one year. The ban covers a wide range of meats, dairy, vegetables, fruit, nuts, seafood, baby food, coffee, and olive oil. According to the Russian authorities, the embargo was designed to “ensure the security of the Russian Federation” and stimulate the development of Russia’s agrarian sector. However, the reality proved the opposite. The ban on food imports drove commodity prices up, reduced the variety of goods available to consumers, and eventually reduced Russian consumption overall.

September: Truce, Elections, and the Relaunch of “Open Russia”

Photo: Brendan Hoffman / Getty Images

By autumn, the military conflict in eastern Ukraine had weakened the Ukrainian forces, which suffered heavy losses. Experts say these losses were the result of Russia’s intense assistance to rebel groups.

On September 5, former Ukrainian president Leonid Kuchma and separatist leaders agreed to a ceasefire. However, the agreement was not sufficiently robust: major concerns remained unaddressed, and the negotiating parties were still far from agreement on a number of key issues. Within hours of the signing of the agreement, multiple violations of its terms were recorded.

On September 14, Russia held regional elections in all of the country’s eighty-four regions. In elections characterized by extremely low turnout and the manipulation and removal of opposition candidates, the United Russia Party won in all regions. Experts point out that the pro-Kremlin candidates’ victory was mainly due to Putin’s high ratings (87%) and electoral manipulation by local authorities.

On September 20, former head of Yukos and former political prisoner Mikhail Khodorkovsky relaunched Open Russia, an organization originally founded in 2001. As he explained in an interview, Open Russia “is a movement directed at influencing state power, at helping the pro-European part of [Russian] society to self-organize.”

October: Total CEO’s Plane Crash in Vnukovo Airport

Photo: Stéphane Grangier / Paris Match

October was a challenging month for Russia. During its first few weeks, the Russian economy set several record lows. The value of the Russian ruble plummeted to 40 rubles against the U.S. dollar and 52 rubles against the euro, which forced the Central Bank to intervene.

On October 20, Christophe de Margerie, CEO of French energy giant Total, was killed in a plane crash at Vnukovo Airport in Moscow. The tragedy of his death was particularly bitter for many, as he was an outspoken opponent of Western sanctions against Russia. With his death, Russia lost not only a business partner and a supporter in the international arena, but also a successful example of a business leader unfettered by politics.

On October 26, pro-European parties won a landslide victory in elections for the Ukrainian parliament.

November: Standoff

Photo: AFP

On November 2, the self-proclaimed republics of Donetsk and Luhansk held elections for people’s councils and governorships. Russia recognized the elections’ results, pointing to their compliance with terms set by the Minsk agreements. However, neither Ukraine nor the Western democracies recognized the elections, declaring them invalid.

Western leaders explicitly demonstrated their disapproval of Putin’s Ukrainian policies at the G20 meeting in Brisbane, Australia. The Russian leader faced such sharp criticism and such a frosty reception from his Western counterparts over Russia’s military adventures in Ukraine that he left the summit early. The official reason for Putin’s departure was “important business back in Russia.”

November was also memorable for the conflict over the “Echo Moskvy” radio station that was settled after a meeting between the station’s editor-in-chief Alexey Venediktov and then—head of Gazprom media Mikhail Lesin.

Finally, recent health care reforms resulted in a mass protest by Moscow medical workers against layoffs and the planned shutdown of a number of hospitals, clinics, and medical centers.

December: The Crisis

Andrey Rudakov / Bloomberg

On December 4, Putin delivered his annual state of the nation address to the Federal Assembly. Many political analysts predicted that this year’s speech would be of paramount historic importance, heralding a “liberal vector” in the face of deepening economic crisis. Alas, Putin failed to offer any appropriate solutions to either Russia’s catastrophic economic decline or a wide range of other geopolitical challenges.

On December 16, the Central Bank was forced to raise its key rate from 10.5% to 17% overnight. Despite this urgent measure, the ruble was still not stabilized. The Russian currency plunged to a historic low of 80 rubles to the dollar and 100 to the euro. Russian stocks crashed as well as people panicked and rushed to buy up foreign currencies on a day labeled “Black Tuesday.”

Putin ignored the ongoing currency crisis, saying nothing on the subject prior to his annual press conference on December 18. Over and over again, his speech disappointed those who anticipated a sober assessment of the situation and a clear plan to overcome the crisis.

On December 30, Moscow City Court found brothers Aleksei and Oleg Navalny guilty in the so-called Yves Rocher case. The verdict was abruptly moved two weeks forward from January 15. It can only be viewed as a part of the Kremlin’s usual manipulation tactic of announcing bad news right before the holidays to mitigate negative public reaction and decrease chances of protests. Aleksei Navalny received three years and six months of suspended sentence, while his brother Oleg was given the same sentence, but it was not suspended.

Heading into 2015, though the economic situation might seem more stable on the surface compared to mid-December, the forecast for the next year is unfavorable. It will be a dark period for Russia: low oil prices, economic recession, foreign isolation, continuing repression of the opposition and growing social discontent.