The Institute of Modern Russia continues the series of articles about Russian nationalism written by the well-known historian Alexander Yanov. The first two essays, dedicated to Pan-Slavism, told the story of the birth of this ideology in Russia. The new installment of the series explains how a great patriotic hysteria led the country to a bloody war for liberation of the Balkan Slavs.

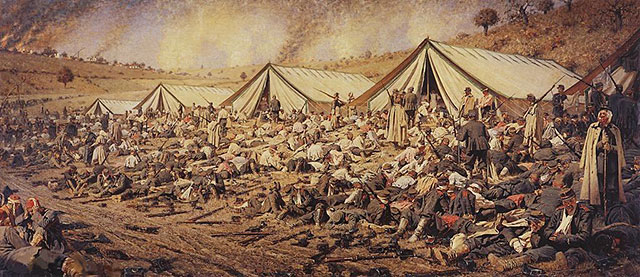

Vasily Vereshchagin. After the Attack. Dressing Station Near Plevna. 1881

I’m fairly certain the reader has guessed that the next incarnation of the Slavophiles (known as Pan-Slavism) played the same role in post-Nicolas Russia as Leninism played in the Soviet Union (under Stalin’s policy of “Socialism in One Country,” of course). This is the role of Russia’s hegemonic idea, to use the language of Antonio Gramsci. In both cases, the state was based on the hegemonic idea of the time, and thus its life and death depended on the idea. Hence why I devote my attention to the birth of Pan-Slavism. You might think it’s a lot of attention. In fact, it is far too little.

That’s just my problem: that I cannot, in the framework of this series, give to the problems of Slavophilism/Pan-Slavism the same level of attention that has been paid in the USSR and in the West to the problems of Leninism. It is clear that this attention disparity can be explained by the differing weights of each famous Russian utopia on the scale of world history. If Leninism embraced both phases of Russia’s Napoleonic complex, both ascending and descending, then Slavophilism/Pan-Slavism got only a secondary, revenge-seeking phase. As a result, it “only” killed Peter’s European Russia, while Leninism split the world. But all the same, the lack of attention paid to Pan-Slavism is insulting to me as a historian of Russian nationalism. All the more so because, without Slavophilism, the world would never have known about Leninism. Have I convinced you of that, dear reader? If you’re convinced, everything else will follow.

There were two main events in the history of Slavophilism/Pan-Slavism: the Balkan War of 1877–1878 and the First World War. We will devote the autumn session to them.

Who Needed the Balkan War?

The Balkan War was conceived, apparently, in the depths of Anichkov Palace, in the residence of the heir—in part, of course, as a response to liberal sentiments in society, but mostly as the first test of the effectiveness of the political union between the nomenklatura and the Slavophiles.

For this they were required to create a great patriotic hysteria and to unleash a small, victorious war to liberate the Balkan Slavs. It was supposed to unite the country on a platform of revenge for the Crimean defeat and to prove to the surging youth Russia’s absolute unselfishness and its willingness to shed the blood of its sons for the sake of its Orthodox brothers. On paper, it sounded simple: “Sire, please come to Moscow in the spring, and hold a service for the Iberian Mother of God, and call the cry: Orthodox! Over the tomb of Christ, over the holy places, let’s help our brothers! All the earth will rise.”

The reality was more complex and much more difficult. And the tsar was less inspired to “call the cry” after the minister of finance explained to him that the war would mean national bankruptcy, and the defense minister explained that the army was not ready for war, and the minister of foreign affairs, Alexander Gorchakov, said that a war with the Turks, in defiance of Europe, would only lead to a repetition of the Crimean catastrophe. As if to arrange it in advance, Gorchakov had one more piece of advice: promise anything to Austria and England.

The patriotic hysteria of 1863 looked like a children’s party compared to what happened in 1876. What the Slavophiles didn’t know was that they were working for Bismarck.

At first, Anichkov Palace, i.e., the “party of war,” had little luck. The Slavophiles especially did not want to hear of any concessions to “Judas-Austria,” “the most artful enemy of the Slavs,” at the expense of the Slavs. Neither were they were enthusiastic about the villainous Albion. And it is clear why: “It’s time to guess,” Slavophile Ivan Aksakov wrote, “that we will not buy the West’s favor with subservience. It is time to realize that the hatred of the West toward the Orthodox world is derived from other, deeply hidden reasons: the antagonism between two opposing spiritual principles and the decrepit world’s envy of the new, which owns the future.”

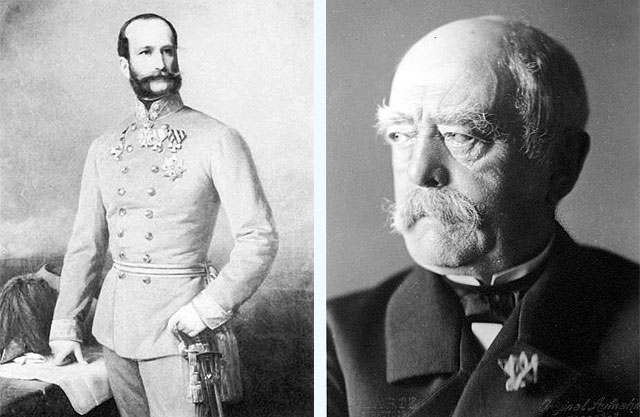

It’s not just that Aksakov, the poor man, read a lot of Pogodin and Danilevsky. That is obvious. He also never realized that the redrawing of Europe as conceived by Pan-Slavists was impossible without the help of “the decrepit world.” To his good fortune (or misfortune), this assistance appeared in the form of the grand master of intrigue and “Russian friend” of European fame, Otto von Bismarck, chancellor of the newly-fledged German empire, which at that moment, for his own reasons, desperately needed a Russian-Turkish war.

On the Road to the War

The role of mediator between Bismarck and the Russian heir was performed by Prince Alexander of Hesse, the Russian empress’ brother, who shuttled from Anichkov Palace to the Reich Chancellery Palace and from there to Vienna and back to Berlin. Finally, it was agreed. England was satisfied with Cyprus, but Austria demanded a hefty chunk of the Slavic Balkans and set a strict condition: that “one big Slavic state” must not be created after the war. All this was, of course, kept a closely guarded secret from the Slavophiles.

Prince Alexander of Hesse (left); Otto von Bismarck

They didn’t have to wait long for a reason to start the war. The Ottoman Empire had a dozen of their own “Polands,” and they rebelled almost continuously. In 1875, Herzegovina rose up; in 1877, Bulgaria. Furthermore, Turkey had been missing its “patriotic hysteria.” The hysteria resumed, and this time it reached such a pitch that a group of patriotic pashas overthrew Sultan Abdul Gaziza, replacing him with the implacable Islamist Murad V. The Bulgarian revolt was the reason for the ferocious massacre that galvanized the whole of Europe. As reported in London’s the Daily Mail: “If we have an alternative—to leave Herzegovina and Bulgaria to the Turkish tyranny, or to give them to Russia, let them take their own—so be it and God bless it.”

Established by Slavophiles in large cities, Slavic charitable committees collected money for the “Slavic cause” in churches. Offices were set up to recruit volunteers to the Serbian Army. There were many of them. They attracted, of course, just wandering people, but there were also retired officers, and young idealists like Vsevolod Garshin. Anichkov Palace dispatched the hero of the Central-Asian military campaigns, General Chernyaev, to Belgrade. He took command of the Serbian Army.

Aksakov’s proclamations denouncing “Asian hordes that are sitting on the ruins of the ancient Orthodox kingdom,” breathed fury. In them, Turkey was called a “monstrous evil and monstrous lie that exists only through the combined efforts of the whole of Europe.” In everyone, such words were seething, tempting hearts and exciting minds, and resulting in an unusual excitement, which the tsar himself could not withstand. The Slavophiles did their part of the job very well. The patriotic hysteria of 1863 looked like a children’s party compared to what happened in 1876. What the Slavophiles didn’t know was that they were working for Bismarck.

The War

On June 30, 1876, Serbia declared war on Turkey. But it did not last long. Three months later, Chernyaev’s troops were routed. The Turks went to Belgrade. Serbia panicked. And what do you think saved it? An ultimatum from “the decrepit world,” which demanded an international conference. Left alone, the Turks retreated. But at the last moment, the conference was interrupted unexpectedly with the announcement that “the sultan bestows the constitution to the Empire, opening a new era of prosperity for all its peoples.” Reassured, European ambassadors left Constantinople.

But in Moscow, patriotic hysteria flared with renewed force: what realignment can there be in the “Asiatic hordes”? The Slavophiles were not satisfied with the bloodless resolution of the conflict, nor even with the Turkish constitution. The Turks were not forgiven for Serbia’s humiliation. The resistance of the “party of peace” was broken. Russia declared war on Turkey on April 12, 1877. Its outcome was predetermined. With extreme effort, the Turks managed to muster 500 thousand men in the field, and half of them were untrained. Their opposition was an army of 1.5 million men. For all that, the war lingered on for almost a year. The small, victorious war did not happen, but the patriotic hysteria did come about, and it was quite big and, as we can see, victorious.

The losses were huge, mainly because of three inept frontal assaults on Plevna (eventually the hero of Sevastopol, Eduard Totleben, took it with a proper siege). The heroic defense of Shipka saved the fate of the campaign, but the victorious army descended from the Balkans in a desperate state. A general staff officer described it as “Our march of victory, achieved by troops that are now in rags, without shoes, almost without ammunition, charges, and artillery.”

Alas, signed in Istanbul’s suburb of San Stefano on February 19, 1878, the peace treaty was even more inept than the planning of the war had been. It provided for the re-creation of the medieval Great Bulgaria, to be the size of half the Balkans—from the Aegean Sea to Adriatic Albania. And on top of this, the land was “temporarily occupied” by Russian troops. But it was the “solid Slav state” categorically forbidden by the secret agreement with Austria. In response, Austria threatened to cut off the Russian Army from its bases in Wallachia. This certainly did look like a treacherous stab in Russia’s back—Serbia, which appeared to have started the war, joined the Austrian protest.

The Berlin Congress divided Bulgaria—which was created to insure Russian influence in the Balkans—into three parts, depriving Russia of all the fruits of victory.

Of course, the Serbs could be understood. A brotherhood is a brotherhood, but they had hoped that the war would recreate a Greater Serbia, not strengthen their old rivals. They also considered the San Stefano treaty a betrayal on Russia’s part. This probably explains why Serbia signed a military alliance with Austria in 1881 and thus became an ally of “Judas” for fifteen long years. It also explains Serbia’s renunciation of Russia after the Russian-Japanese War in 1905, and its attack on Bulgaria in 1913, in alliance with its bitterest enemy, Turkey. It is scary to think what would have happened with Aksakov had he lived through this series of Serbian betrayals and the massacre among Slavs.

And then, following the conclusion of the war, Bismarck showed his teeth. At the Congress of Berlin in June 1878, says a French historian, “Shuvalov and Gorchakov, to their great astonishment, have not found Bismarck’s favoritism to Russia, on which they counted, not the slightest support in anything.” Now, the Slavic passion that Bismarck had so carefully stirred up with the help of the dull heir to the Russian throne was no good to him. He had achieved his goal. He became the European peacemaker; now Austria, having taken the bait (a piece of the Slavic Balkans), was in his pocket, and Russia was farther than ever from Constantinople (and would still have to face Romania, which was mortally offended that Russia had taken Bessarabia away from it).

Results

The Berlin Congress divided Bulgaria—which was created to insure Russian influence in the Balkans—into three parts, depriving Russia of all the fruits of victory. Austria got Bosnia and Herzegovina, and England got Cyprus, without firing a single shot. And what was Russia left with? She remained with what she had. After a war that almost led her to bankruptcy, after tens of thousands of solders were killed in Plevna, after all her hopes and expectations for the Slavic Union, and with the Russian Army now located in the vicinity of seductive, coveted Constantinople—after all this, she was to be left with nothing?

“It was the bitterest chapter in my biography,” an aged Gorchakov said to the tsar after the Berlin Congress. “And mine too,” said the tsar. Aksakov burst into the thunderous article “Is it You, Russia?” cursing, of course, “a decrepit world,” which had taken from Russia “the winning crown, presented in return the foolscap with rattles, and [Russia] obediently, almost with an expression of sensitive gratitude, bowed suffering head under it.” It was a time of cosmic mourning.

Wait a minute, though. What was the reason for the mourning? Was it not the Slavophiles who called upon Russia to fight against the “Asian hordes” for the release of their Orthodox brethren? And didn’t they prevail? Did not Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania gain independence after the Congress, and Bulgaria its autonomy? Was it truly a “foolscap with rattles”? Where was this lamentation by the waters of Babylon coming from? Was Austria given the chance to grab its “fair plentiful kill” in the Balkans, while Russia was not? It was not Austria that had vowed that it needed nothing but “the Christian truth,” as Russia had. But judging by the mourning, “the Christian truth” was not enough. Why do you think?

***

Shortly after the Balkan debacle, the philosopher Vladimir Solovyev asked: “Was it worth it for to Russia to suffer and fight for a thousand years, become a Christian country with the Holy Vladimir and a European country with Peter the Great, just to eventually become the instrument of a Serbian great idea or a Bulgarian great idea?” Unfortunately, Russia did not hear him. And three decades later, she repeated all the same mistakes she’d made in 1870, and was again embroiled in a war for the sake of “the common faith and the consanguineous” Serbia (as was written in the tsar’s manifesto). With a difference: the puppeteer was not Bismarck, but rather the French President Raymond Poincare. And the outcome of this one was fatal.