With the erection of a monument in the center of Moscow this coming September, Pyotr Stolypin, Prime Minister of Russia (1906-1911), is to be memorialized by Putin's regime on the 100-year anniversary of his assassination. Historian Alexander Yanov puts this glorification of Putin's favorite historial figure in perspective, highlighting Stolypin's brutal and autocratic policies that paved the way for the Bolshevik terror—and beyond.

From left to right: Vladimir Putin next to the foundation stone for the Stolypin monument; the official portrait of Pyotr Stolypin.

We are standing on the eve of two anniversaries: 2012 marks 150 years since the birth of Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin and 100 years since his assasination. Unlike with the recent anniversaries of the symbols of Russia’s 19th liberal tradition, namely, Alexander Herzen and Mikhail Speransky, we can rest assured that Russian authorities will commemorate Stolypin with great pomp. By September 11th, 2012 (the anniversary of his death), the government will make sure to have his monument erected on the Krasnokholmskaya Embankment. Its cornerstone was laid this spring in a meaningful gesture by none other than the current (and former) President of Russia, Vladimir Putin. Stolypin is his personal role model. The Russian media is sure to make much of this celebration.

Before the pageantry begins, I would like to add a few brushstrokes to the portrait of Putin’s favorite historical figure by mentioning the aspects of his policies that will not be emphasized in the course of the official celebration.

This celebration was conceived partly as a response to the recent protest rallies staged by the so-called New Decembrists (labeled “bandar-logs” by Vladimir Putin, in attempts to smear them). Meanwhile, Stolypin himself never went after his liberal-minded fellow Russians, although he admonished them. However, he always did so in a dignified manner, saying, “You are seeking a great upheaval, when what we need is a great Russia.” And in spite of the glaring differences in the tenor of their pronouncements, I believe that Putin would throw this kind of gauntlet to the protesters if his manners came from the school of aristocracy rather than the streets of Soviet-era Leningrad.

It is worth noting that the Soviet Encyclopedic Dictionary (used as a reference at the KGB school where Putin continued his education) characterized Stolypin somewhat critically. It did not mention his words on the great Russia, but said the following about our hero: “[Stolypin] determined government policy during the Age of Reaction (1907-1911). He was the organizer of the counter-revolutionary coup of June 3, 1907.”

Soviet verbiage aside (“counter-revolutionary” etc.), one cannot deny the basic fact: Stolypin was the mastermind behind the anti-constitutional coup of 1907. “Stolypin neckties” (as nooses were called by a liberal lawmaker of the time, in reference to Stolypin’s decree mandating capital punishment by hanging alleged terrorists) became part and parcel of Russian political folklore. This is precisely the point where the image of Putin’s hero loses its integrity and begins to resemble a kind of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, as blood stains emerge on the white gloves of this irreproacheable defender of the Great Russia. This other side of Stolypin’s political persona became more prominent with the famous story written by Leonid Andreyev about seven people charged for plotting the assasination of a government official and hanged by the decision of a ‘troika’—three military field officers—in accordance with Stolypin’s decree, mentioned above. Of course, the total number of such executions under Stolypin was not seven, but six thousand. Strangely enough, the decree was never submitted to the Duma for approval.

If Tolstoy is to be believed, the “moral decay of all the strata of Russian society” and executions without due process, staged “under the pretext of some necessity and common good," prepared the Russian psyche for the Bolshevik terror, which took place a mere decade later, in a country that truly had succumbed to "moral decay."

After Soviet mass executions of the officers of the former Imperial Army by Lenin’s CheKa (the forerunner of the KGB) in the course of Russia’s Civil War (1918-1920), Stolypin’s executions may seem negligible. However, let us keep in mind that Stolypin’s neckties were before, not after, the CheKa massacres. And it was under Stolypin that Russian society accepted mass executions without due process as a fact of life. Or at least this was how these executions were interpreted by Leo Tolstoy. In his anti-Stolypin pamphlet I Cannot Remain Silent! Tolstoy writes, “In addition to the direct harm to victims and their families, all of these acts of violence and murder cause even greater harm by spreading the moral decay across all strata of Russian society and spreading it fast—like fire on dry straw. This decay spreads with particular speed among the simple working people because all of these crimes–dwarfing the thieves’, the gangsters’, and all of the revolutionaries’ taken together—are being committed under the pretext of some necessity and common good.”

Although Tolstoy couldn’t have known how true his words would be, Stolypin’s “moral decay of all the strata of Russian society,” his executions without due process, staged “under the pretext of some necessity and common good,” turned out to have been training of sorts, preparing the Russian psyche for the Bolshevik terror. Within ten years of Tolstoy’s writing, this terror would strike the country that truly had succumbed to moral decay.

Digression Into Current Events

I can only imagine the outrage of Russia’s newly-appointed Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky if he reads this unvarnished, demystified portrayal of Stolypin, with “warts and all,” to use an American expression. Medinsky was appointed in light of his record of fighting against the “myths” in Russian history, all of these blood-stained “warts” (i.e. against anything that does not fit the interpretation of history that can be used by the authorities to justify their actions). By his own admission, Medinsky already made millions while struggling toward this hard-won end. Then suddenly—what a scandal!—Putin’s historical hero turns out to be covered in bloody warts! And this, shortly before the monument is to be unveiled. Who is going to be held responsible, if not the minister whose duty it is to defend our nation against “myths”?

Furthermore, in this case, Medinsky’s trademark dismissal of the issue (“all of this is another myth”) won’t suffice. There is too much evidence, namely, hundreds of newspaper articles. Stolypin had tried his best to defuse the scandal in his time. Indeed, he had 206 newspapers shut down and brought charges against their editors in chief. But there was no way he could silence Tolstoy, and the writer’s cry of horror was heard around the world.

Medinsky has another trick up his sleeve. Yes, he could admit, in 1906, when Stolypin came to power, the revolution was dying of natural causes, but there were still some terrorist "leftovers" that had to be liquidated (“terror” in this context refers to individual assasinations of government officials practiced by some factions in the revolutionary movement). So, Medinsky would say, these people had to be sent to the gallows – what else could have been done? The executions were a necessity, they were done for the right cause – isn’t that an argument?

Yes, except that Tolstoy had already answered that question. There were not six thousand “terrorists” in Russia. Capital punishment was served to everyone suspected of terrorism. The executions took place on the basis of unverified reports, without due process. Even if there were a few terrorists among those hanged, who can say how many innocent people just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time? And whose hands were soaked in the blood of these innocents?

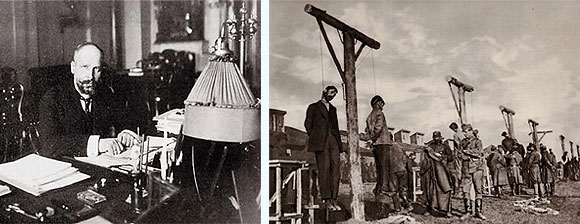

From left to right: Pyotr Stolypin in his office in the Winter palace, 1908; the gallows—"Stolypin's neckties".

Evidently, Medinsky has just one last argument at his disposal, one that is familiar to Russians as the same argument used to justify the CheKa terror, “You have to break a few eggs to make an omlet.” In the end, Stolypin achieved his goal: he did away with revolutionary “leftovers,” and winners are always in the right. The ends justify the means. The erection of a monument in the center of Moscow, with the first stone laid by the successor of the CheKists, is a gesture acknowleding that the current government approves of terror and subscribes to its same principle—the principle of politics without morality.