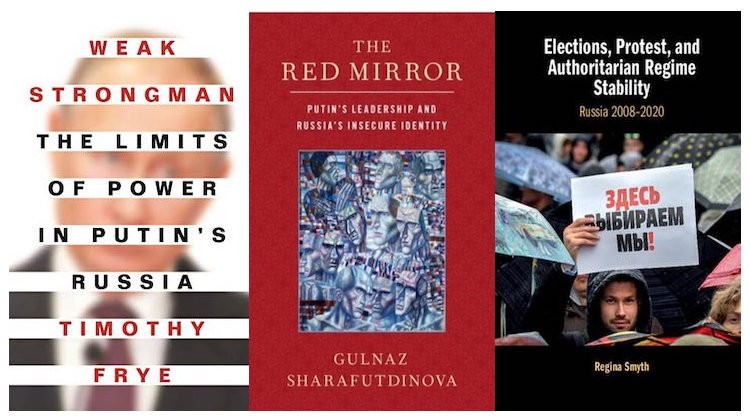

On May 21, the Program on New Approaches to Research and Security in Eurasia (PONARS Eurasia) hosted an event titled “Putin’s Strengths and Vulnerabilities: Three New Books.” The authors, Regina Smyth, Timothy Frye, and Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, shared new perspectives on Russian society, opposition, and Putin’s presidency in the last twenty years, taking academic concepts and putting them in context for a broader audience. IMR has summarized these three authors’ arguments, highlighting new perspectives on existing narratives and the reasons why these books are relevant to understanding Russia today.

The event's livestream can be found here. Photo: PONARS Eurasia.

Elections, Protest, and Authoritarian Regime Stability: Russia 2008–2020

Regina Smyth, Professor of Political Science at Indiana University

Smyth spoke about the role of the opposition in Russian elections and why, although the opposition keeps running and organizing, it hasn’t managed yet to shift Putin. The opposition still plays a vital role in Russian politics and the Kremlin is constantly working to mitigate and undermine its effect.

Her work studied Russian elections from 2008–2020, demonstrating how political opposition can force autocratic incumbents to rethink strategy and find compromises in order to win elections. This book highlights the vast resources the Kremlin expends to maintain a “permanent campaign” to keep their regime-friendly majorities winning.

Does the study of opposition voting matter if you know who will win? To address this question, Smyth’s book puts social science tools in a real-world context and analyzes true support for the regime and the opposition, revealing a lot about what Russia believes about its politics. One reason the opposition politicians still run, even though they know they won’t win, is because they can reveal otherwise hidden support.

The opposition has taken a stand against the Putin regime in multiple ways in the last dozen-plus years. One way is through election boycott, as seen when Alexei Navalny snubbed the 2018 elections. But this is “messy” because it is impossible to tell from the election results whether voters are alienated or making a statement. A more clear-cut method for analysts is when the opposition politicizes the process of elections, such as when Navalny ran for mayor of Moscow in 2013 and in doing so created a new campaign model. The regime knew he wouldn’t win, but his campaign built national interest and name recognition across the country. The opposition can also take a stand in the voting process by leading initiatives to vote against all candidates down the ballot, spoiling ballots. In one case, the opposition used a strategic voting app (“smart voting”) to coordinate votes for candidates that could undermine the regime and bring about change. make responsive change.

The biggest change since 2008, according to Smyth, is that there is literally no opposition left on the ballot in Russia. Societal capacity for opposition is increasing, as is the pool of voters. The pro-Kremlin United Russia party has failed to build ties with voters or a policy-based connection, focusing on control and little else. Smyth predicts that in the September election, the cost of victory will be high.

Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia

Timothy Frye, Professor of Post-Soviet Foreign Policy at Columbia University and a research director at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow

Frye argues that there is much the West overlooks about today’s Russia when focusing on the two most common ways of thinking about Russian politics: first, Putin, and second, Russian exceptionalism—the idea that Russia has a unique history and culture. He argues that Russia is remarkably similar to other autocracies, and recognizing this illuminates the inherent limits to Putin’s power.

Although offering, at heart, a social science perspective on Russia, Frye said he wanted to deliver a general interest book to appeal to those who are “Russia-curious,” get beyond often simplified reporting, and add context. Frye believes most people have fairly strong views on Russia, so he has “done his job” if his book generates more nuance or perspective, and people pay more attention to Russia’s society in comparative terms.

Frye stressed the need to have a contextualized perspective on Russia. He categorizes Russia as a personal autocracy whose governance follows patterns of politics in other “personalist” autocracies but differs from military- and party-led autocracies. This categorization starts to correct the view that Putin is omnipotent because he faces no challenges in the political arena. On the contrary, he does face opposition, and there are “constraints and trade-offs” the Kremlin needs to deal with.

The Kremlin often manipulates elections to gain a majority, but it can’t engage in too much of what looks illegitimate. The Kremlin manipulates news and media, but not in a way that goes too far, or causes people to stop watching. It represses political opponents but not so much as to spark a political backlash; it uses corruption to help its cronies but not so much that it leads to protests and economic backlash. The Kremlin engages in provocations in foreign policy, using anti-Western rhetoric in talks within the administration, but not so much that it leads to war.

In his research, Frye utilized diverse methods, including survey techniques to see if people lied about their support for Putin; examining Russian electoral data to detect fraud; conducting archival research to see how purges affect current voting patterns; and examining graffiti in Moscow to look at patterns of protest.

To guard against the book being seen as a niche economic–social science analysis, he included many personal anecdotes and stories, starting when he worked for the U.S. information agency in the Soviet Union in late 1980s, a security exchange commission in Moscow in the 1990s, and at the Higher School of Economics in recent years. He believes these stories provide insight that is hard to come by unless you spend a lot of time on the ground in Russia. Frye wants to “turn the temperature down in the discourse about Russia.”

Red Mirror: Putin’s Leadership and Russia’s Insecure Identity

Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, Reader in Russian Politics at King’s College London

Sharafutdinova uses social identity theory to explain Putin’s leadership and enduring popularity in Russia. She argues that the main source of Putin’s political influence is how he articulates the collective perspective that Russians hold. Putin has tapped into powerful group emotions derived from the Soviet transition in the 1990s and has politicized national identity to transform feelings of shame and fear into feelings of pride and patriotism. Culminating with the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Putin’s strategy of national identity politics has come to define his leadership.

Sharafutdinova’s book was a personal endeavor driven by questions about the growing gap in Russians’ own knowledge of Russian politics, and the increasing difference in how the West and Russians perceive the Russian state, especially after 2014.

She set about integrating research methods from the fields of history, political science, and social psychology to understand this gap and why it continues to widen. To find out if cognitive models from past Russian periods still affect perceptions today, she used, for example, the idea of the “Soviet man” (homo sovieticus) that was revived after the Crimea crisis, and found that “the whole concept is driven by outdated analytical foundations.”

Insights came from looking at social identity theory, which involves group identity, belonging, and in-group perceptions. Social identity theory requires a lot of context—it’s a process that connects leaders and followers, in this case Putin and the Russian people. Putin has made the most of the social and cultural context he inherited. He uses pillars of Soviet intellectual theory: a sense of Soviet exceptionalism, the role of conflict, and the ever-present sense of an enemy. Sharafutdinova argues that the Kremlin weaponized the collapse of the Soviet Union and the hardships of the 1990s to cause collective trauma and thereby reactivated the three pillars. The Kremlin consolidated leadership around Putin—a strategy that reached a high point after the annexation of Crimea.

Sharafutdinova notes how relevant this theory is, bringing up a May 21 Reuters report that Putin threatened to “knock out the teeth” of foreign aggressors, saying “everyone wants to ‘bite’ us somewhere or ‘bite off’ something of ours.” This reaction highlights the insecurity of Russia, the idea that the nation is perpetually surrounded by international enemies, while encapsulating Putin’s role as leader and protector.

* Liya Wizevich is a leadership team member at the Stanford U.S.-Russia Forum. She holds B.A. in Russian and East European Studies from the University of Pennsylvania and M.Phil. in History from the University of Cambridge.