In recent decades, China and Russia have both experienced ample economic growth, but have achieved it via diametrically opposed paths. Whereas China has pumped spending into infrastructure and investment, Russia has fed export revenues into wage growth. Now that Russia has entered a deep recession, is China winning? In the concluding installment of a three-part series on the BRIC nations, IMR analyst Ezekiel Pfeifer compares the economic prospects of China and Russia.

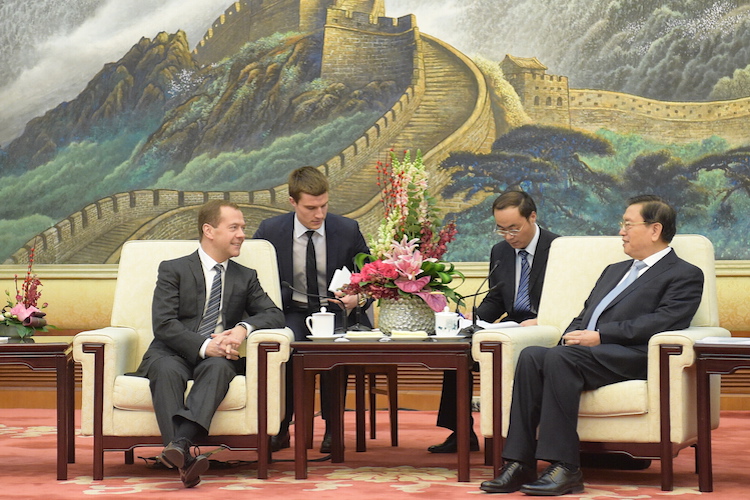

Russian Prime Minister's official visit to China marks twenty years of regular annual bilateral summits. Dmitry Medvedev (left) at the meeting with Zhang Dejiang (right), chairman of the standing committee of the National People's Congress of China on December 16, 2015. Photo: Alexander Astafyev / TASS

In recent months, many observers of China’s economy have made bleak predictions about its future. Over the near term, there is a 55 percent chance of a “made-in-China” global recession, Citigroup’s chief economist said in September. Prices for Chinese manufactured goods, the lifeblood of the country’s export-dependent economy, have been dropping in real terms—for 43 straight months. Beijing insists that GDP growth stands at around 7 percent, but most economists dismiss the government’s figure as artificially enlarged. (One professor at a Hong Kong university said it was “anybody’s guess” how China determines its GDP number.)

The concern can seem hyperbolic when you compare China’s official GDP growth to economic expansion worldwide, which the International Monetary Fund projects to be 3.3 percent in 2015. Only a few dozen countries have growth rates comparable to China’s, and many of those nations are in impoverished Central Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, which have farther to climb. But watchers of China’s economy are not comparing the country’s growth to the rest of the world. They’re comparing it to China’s past. And over the last 25 years, the country’s GDP has averaged approximately 10 percent annual growth, an extraordinary feat known as the Chinese economic miracle.

The word “miracle” implies that the surge occurred by chance, but China did not win a special lottery or receive a holy blessing to achieve its growth. Instead, it used the tools that are often necessary for success: blood, sweat, tears, and economic policy. National culture and history have almost certainly contributed as well (along with, it’s surely true, a bit of luck). The relevant question for Russia and fellow middle-income countries around the world is: What aspects of China’s model have allowed the nation to flourish?

On the surface, China and Russia have much in common. Both have deep legacies of Communist rule but have increasingly embraced market mechanisms, while retaining state control over significant portions of the economy. Both countries are both spread across massive, diverse physical territories. They both rely heavily on export revenue to fuel their economies.

But in terms of economic policy, the two nations have taken diametrically opposed paths. Whereas Russia has relied on frequent wage increases and consumer spending to drive growth, China has spent trillions on infrastructure, real estate, and industrial capacity. (As Carnegie Endowment experts Yukon Huang and Patrick Farrell have noted, China’s model is not exactly new—it is similar to the path taken in recent decades by Asian Tiger nations like South Korea and Taiwan.) Russia’s export revenue mostly comes from the sale of oil, gas, metals, and timber; China earns much of its money from sales of manufactured products, made cheaply by the country’s enormous labor force.

Growth in China over the last 25 years has been more consistent than in Russia, which suffered seven years of economic contraction during the 1990s, following the Soviet collapse. But the Asian behemoth is nonetheless playing catch-up: per capita GDP in Russia stands at $12,736, while in China it is at $7,594. So, can we say that one country’s model has really been better than the other’s?

Overall, China has taken the approach of “Build it and they will come.” The world’s largest shopping mall opened in the southern city of Dongguan in 2005—behemoth shopping malls have become popular all over China. In the northern city of Tianjin, a financial district meant to mimic Manhattan awaitsresidents, one of a rising number of Chinese “ghost towns.” China’s gross capital formation, a measure of nationwide investment spending, was a whopping 48 percent of GDP in 2013, compared to Russia’s 23 percent of GDP—less than half the total of China. Overcapacity has become a problem as worldwide demand flags. The outlays on infrastructure and industrial production have been possible in part due to China’s sky-high savings rate of 50 percent (fourth-highest in the world in 2013). Russia’s rate of 24 percent is closer to the middle of the pack and reflects Russians’ tendency to spend when they have spare cash, due in part to their sense that the future is uncertain.

Indeed, consumer spending, as well as oil sales, have spurred much of Russia’s growth over the last 15 years. Household expenditures have held steady at around 50 percent of GDP in Russia since the early 2000s, while in China the 2013 total stood at 36 percent of GDP. (Interestingly, spending on imports in the two countries is comparable, having ranged from around 19 percent to 23 percent of GDP in recent years.) Both countries have now reached a turning point in their development, however, and appear eager to pursue the other’s previous path of economic growth.

In Russia, the worldwide collapse in commodity prices has triggered sustained weakness in the ruble, producing new potential advantages for Russian manufacturers. In July, for instance, the average monthly salary in Russia stood at $591, compared to $775 in China, a difference that could convince international firms to open labor-intensive facilities in Russia. The Kremlin is counting on such trends to reverse its deep economic slump and help it overcome Russia’s structural flaws (in particular, the fact that oil and gas proceeds make up approximately half of all tax revenue and potentially represent an even larger portion of the economy on the whole).

Given Russia’s precarious political and economic situation, it seems fair to declare China better-positioned to thrive going into the future. The main risks to its further rise may come from the consequences of the state’s tight control over the political system and its refusal to give freer rein to the economy.

At the same time, China is seeking to boost domestic consumption to use the massive capacity it has created. (In other words, now that they have built it, they need people to come.) And consumers appear increasingly willing to oblige by dipping into their wallets: retail sales were up 10.5 percent as of late September, a figure that does not include services. On Singles’ Day, Alibaba’s answer to Black Friday, the Chinese online retailer sold $14.3 billion worth of merchandise, a 60 percent increase from 2014. Consistent wage growth—currently it stands at 7 percent, matching GDP expansion—has contributed to the spending boom.

Given Russia’s precarious political and economic situation, it seems fair to declare China better-positioned to thrive going into the future. The main risks to its further rise may come from the consequences of the state’s tight control over the political system and its refusal to give freer rein to the economy. Can China sustain its advantages with such a restrictive model of governance?

In 2013, China’s leadership announced that it would cede more power to market mechanisms, but the government has yet to make good on the pledge. It blatantly manipulated the overheated Shanghai stock market over the summer to halt wild price swings, and in the process spooked international investors. A long-awaited plan to reform state-owned enterprises, published in September, disappointed many observers, since it is did not envision transferring control of the sprawling sector to more efficient private ownership. With billions upon billions of dollars on the line, vested interests in China place enormous pressure on the government to maintain the status quo, as in Russia.

Like Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping has played a decisive role in strengthening the country’s role in the world but has not focused his efforts on improving the economy. He has taken certain important steps, such as leading an anti-corruption campaign that has targeted high-level officials, including a former politburo member. Putin, by contrast, has steadfastly refused to halt the schemes of top Russian officials, perhaps because Putin himself and many law enforcers likely participate in such schemes. Also, while the Chinese Communist Party has refused to give up its monopoly on power, it has maintained the institution of a consistently rotating presidency for more than three decades. That institution, which Russia has essentially abandoned in the Putin era, allows for some rotation in the ranks of the elite and may enhance societal stability.

Even so, China will likely need to loosen its strict social controls eventually to maintain growth, or face a violent backlash on a scale equal to or greater than the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square. Russia may face a similar fate if it does not provide the opposition an opportunity to develop. But, with Russia increasingly overextended by the conflict in Ukraine, its intervention in Syria, and the recessed economy, China appears to be on a more level footing overall. Perhaps the Chinese “economic miracle” will come to an end, but it is unlikely to turn quickly into catastrophe. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about Russia.

Follow the links to read part one (Brazil) and part two (India) of the series.