The Institute of Modern Russia continues its series of articles by well-known scholar Alexander Yanov on the history of Russian nationalism in the USSR. In this essay he writes about the consolidation of the right-wing opposition in its struggle against cosmopolitanism and its diminished enthusiasm as a result of the measures taken during the Brezhnev regime that followed.

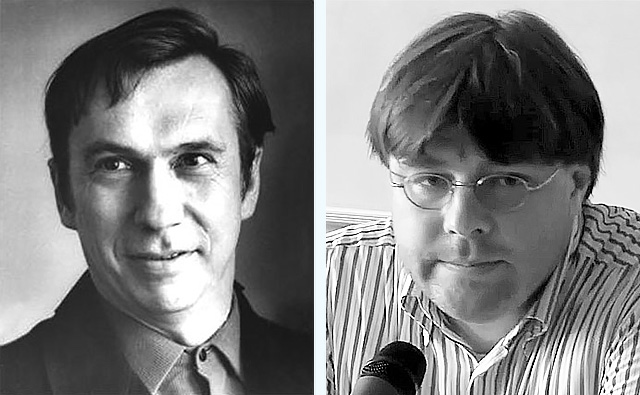

Sergei Simanov, the Russian Party’s “grey eminence” (left) turned out to be the most eloquent interviewee of a Moscow-based historian Nikolai Mitrokhin, author of The Russian Party. Movement of the Russian Nationalists in the USSR, 1953-1985.

In retrospect, the story of the downfall of Novy Mir (New World) magazine, edited by Alexander Tvardovsky, was quite typical for its time. In 1969, in its 30th issue, Ogonyok magazine, which was a fundament for the conservatives of the moment, published an article titled “What Does New World Stand Against?” It was a public denouncement of Novy Mir signed by eleven “prominent” writers. More accurately, they were prominent in the realm of socialist realist literature, but hardly anyone remembers the names of Vytaly Zakrutkin or Sergei Malashkin today.

The public denouncement read, “Despite [Alexander] Dementyev’s persistent appeals to not overestimate the danger of alien ideological influence, we claim again that the pervasion of bourgeois ideology remains the most serious danger and might lead to progressive replacement of concepts of proletarian internationalism with cosmopolitan ideas, which are so dear to some critics and authors who are close to New World” (emphasis mine). Collective letters were not favored in those times—indeed, they were strictly punished. But as an exception, that denouncement was taken into consideration and resulted in a fatal ultimatum for Tvardovsky.

This outcome came as no surprise. The denouncement had alluded to the magic word “cosmopolitanism,” which had been widely used in Stalin’s times. Anyone familiar with the ways of the Soviet ideological establishment could understand how two people as different as Anatly Sofronov and Sergei Vikulov—the editors of the conservative pro-Stalin magazine Ogonyok and the nationalist magazine Nash Sovremennik (Our Contemporor) respectively—could unite against “cosmopolitanism.” The word also explains how Novy Mir managed to oppose pro-Stalin conservatives for such a long time.

Consolidation of the right-wing opposition

Stalinists were obsessed with their perceived struggle against “cosmopolitanism”; ideological heresy; and their opinion that the country owed its victory in World War II to the governing genius of its Caesar (Stalin). Following Stalin’s death and Khrushchev’s Thaw, though, all those Stalinists began feeling isolated. To take revenge, former first secretary of the Komsomol Central Committee (from 1952–1958) and ex-chairman of the KGB (from 1958–1961) Alexander Shelepin united with Leonid Ilyichev, chairman of the Ideological Commission of the Communist Party’s Central Committee in 1962.

Having become a member of the Politburo, Shelepin tried to turn Khrushchev against the liberal intellectuals and the young writers. Though his efforts were unsuccessful, he later managed to actively participate in the ousting of Khrushchev. Shelepin can’t take all the credit for that, though; the majority of the credit goes to the center-rightist Leonid Brezhnev and his so-called “Dnepropetrovsk mafia.” (Brezhnev was born in the Dnepropetrovsk region of Ukraine and, once he became secretary general of the USSR, he brought many of his Dnepropetrovsk comrades to the Kremlin.) Vladimir Semichastnyi, who succeeded Shelepin as the head of the Komsomol and the KGB, complained later that “it was almost absurd: [Premier Alexey] Kosygin had five deputies—all coming from Dnepropetrovsk. There was a come-true popular joke in Moscow at the time regarding the new periodization of Russian history: a pre-Peter period [Peter I], Peter’s period, and now—Dnepro-Peter’s period.”

As a result, the Komsomol and KGB team assembled by Shelepin turned out to be useless. But the fatal blow to the team was dealt by Marshal Georgyi Zhukov, who, in his memoirs, accused Stalin of causing the 1941 disaster (the unexpected attack of the German Nazi troops on the Soviet Union in June, 1941, that resulted in great losses). Marshals Konev, Bagramyan, and Golovanov, who published their memoirs in Oktyabr (October) magazine and Molodaya Gvardia (Young Guard) magazine, tried to argue with Zhukov, but appeared helpless against the legendary commander’s statements.

Under the circumstances, Shelepin’s attempt to remove Brezhnev in 1967 seemed an act of despair. The Stalinist group in the government had been crushed down: the secretary of the Moscow Committee of the Communist Party Nikolay Egorychev was transferred as an ambassador to Denmark; the chairman of Gosteleradio (Soviet state television and radio) Nikolay Mesyatsev, as an envoy to Australia; and head of the department of the Communist Party’s Central Committee Vladimir Stepakov, to Yugoslavia. Shelepin himself was transferred to oversee trade-unions.

Stalinists urgently needed additional support, since they couldn’t take down Tvardovsky all by themselves. Meanwhile, the Russian Party, which had just entered the country’s political life, was looking for a way to become a legitimate part of the ideological mainstream. And such legitimacy would only be possible through a union with the Stalinists. Dementyev’s failure that we covered in the previous essay, gave the Russian Party a reason to unite with the Stalinists upon the ground of a resurrection of Stalin’s mantra on the dangers of “cosmopolitanism.”

Two mythologies

Such was the background against which a newly consolidated right wing of the Soviet nationalists managed to oust Tvardovsky from Novy Mir. To understand how exactly their consolidation proceeded, one should look into the book titled The Russian Party: Movement of the Russian Nationalists in the USSR, 1953–1985 by Moscow-based historian Nikolay Mitrokhin. The author challenges the two most common descriptions of the internal political life of the post-Stalin USSR—the “liberal mythology” and the “nationalist mythology.” He introduces liberal mythology as “a union of ‘good people’”—(in the first articles of our series I termed them “Russian Europeans”)—“who in the 1960s were united by the slogan [from a popular song by Bulat Okudzhava] ‘let’s join our hands my dear friends, we won’t get lost if we’re together,’ a slogan that had been validated by dozens of years spent in kitchen-talks, tourist hiking, and re-typing copies of Anna Akhmatova’s poem ‘Requiem’, and that seemed to be the only ideological force in the country—to those who supported it.”

Meantime, Mitrokhin continues, parallel to the liberal movement in the USSR there existed another opposition movement: Russian nationalists. “It was a well-organized community of like-minded people who could advocate their ideas not only in creative unions but also through the government’s machinery. It gained protection from some representatives of the Politburo; dozens of employees of the Central Committee became its members.”

Anti-Semitism, inherited by the post-Stalinist Russian Party from the pre-tsarist generation, was its essential feature, a sort of trademark to distinguish “friends” from “foes.”

I wrote about the nationalist opposition to Stalin’s regime in my book The Russian New Right (Berkley, 1978), twenty five years before Mitrokhin. But Mitrokhin’s work has one serious advantage: during the Perestroika years, he managed to conduct about fifty exclusive interviews with “commanders” and regular members of the Russian Party, having introduced himself as a “sympathizer.”

In his book, Mitrokhin targets the “liberal mythology,” but he criticizes the nationalists even more: “Their rough anti-Semitic spirit might surprise those who think that Russian nationalists were only concerned about protecting Russian cultural heritage, the country’s ecology, or propagating ‘spirituality.’”

Anti-Semitism, inherited by the post-Stalinist Russian Party from the pre-tsarist generation, was its essential feature, a sort of trademark to distinguish “friends” from “foes.” In the end, Mitrokhin reduced his description of the Russian Party to ethno-nationalism, although this wasn’t the only role of the party in the political life of the post-Stalin USSR. The core of the party consisted of conservative alternatives to Brezhnev’s status quo. And the regime understood this very well, regularly striking out at both liberals and nationalists.

The opposition is shown its place

Sergei Semanov, a “grey eminence” of the Russian Party, was most eloquent in his interview with Mitrokhin. He hardly ever spoke publicly, but was very well informed about the party’s affairs. Here is a key excerpt from his interview:

“Young Guard magazine placed its biggest stake on enlightenment of the bosses (or more accurately, the ‘deputy bosses’). The environment was free and friendly: everyone who didn’t marry in Brezhnev’s style—” (Brezhnev’s wife was thought to be Jewish, an assumption that served as an explanation for his absolute indifference to the “Russian cause”) “—and wasn’t under the influence of the ‘wise men,’ seemed rather sensitive to Young Guard’s ideas—and this was the fair majority of the upper ruling class. The ideas of the national character, order, traditionality, and rejection of destructive modernism of any kind—they all matched the beliefs of the fundamental part of the post-Stalin political elite… The majority of Russian intellectuals in the 1970s… remained more or less within the mainstream of cosmopolitan liberalism. At that time, Young Guard’s audience was chosen correctly in terms of political perspectives: dismissing the ‘key circles of intelligentsia,’ the magazine addressed the [Communist] party’s middle class, the army, and the [common] people.”

Who were the “deputy bosses”? Viktor Golikov, the general secretary’s aide; Vladimir Vorontsov, aide to the Communist Party’s ideologist Mikhail Suslov; Gennady Gusev, aide to the Politburo member Vitaly Vorotnikov; Vasily Shauro, head of the Central Committee’s department of culture; Sergei Trapeznikov, head of the department of science and educational institutions; and Gennady Strelnikov, aide to the secretary of the Central Committee in matters of science, who later became aide to the minister of culture Pyotr Demichev. (There was a rumor that artist Ilya Glazunov even used to hide copies of the prohibited nationalist underground magazine Veche at Strelnikov’s place—we’ll discuss this magazine in the upcoming essays of our series). Hardly anyone remembers these people today, but at the time, the lives of thousands of people depended on them.

Essentially, these people formed the so-called “krysha” (criminal slang for “roof” or protection) for the Russian Party. They could allow a campaign against “Chalmaevshchina,” or help to legitimize Young Guardsmen by reconciling them with Stalinists. They had the power to lobby an appointment or resignation of a head of an institute or laboratory. As we have seen, they could also oust Tvardovsky. But they weren’t almighty, and Young Guard magazine was about to see this.

In his article titled “About the Values, Relevant and Eternal,” Semanov made another bold move to support the Stalinists, supposedly as a thank you for their support in the ousting of Tvardovsky. The article was written in order to secure the achievements of “Chalmaevshchina,” and it abounded with odes to the “national spirit” and “traditional values.” The October Revolution was named as “Russia’s national pride”; Generalissimo Stalin was hailed as the creator of the Russian Victory (in World War II); and “the deepest disdain for our people, its traditions, its history” was denounced as the “first sin” of Trotskism.

But the main and unprecedented statement of this article was as follows: “After the adoption of Stalin’s constitution, the mid-1930s became the turning point in the struggle against destroyers and nihilists, when all the honest-working people of our country grew to be molded together into one solid whole, now and forever.” Following Khrushchev’s denouncement of Stalin’s personality cult at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, the 1930s—the era that Semanov spoke of, the era of “black crows” (prison vans) and total terror—was one that he suggeseted should be buried in oblivion. Even the official historiography described this period using terms like “Ezhovshchina” (the Great Purge implemented by Nikolai Ezhov, head of Stalin’s secret police) and the “slaughter of party members.” And here was Semanov openly calling this darkest period (darkest not only for the “key circles of intelligentsia,” but also for the ruling party and the secret police itself) a bright celebration of the “national spirit,” the beginning of the “unity of our people.”

This was indeed a clumsy assistance to the Stalinists. In saying that “those changes had the most beneficial impact upon the development of our culture,” Semanov was trying, of course, to overrule the decisions of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party and to rehabilitate Stalin. From the Stalinists’ point of view, his intentions were good, but his implementation was awful. Romanticizing the Napoleon-like legend of “our generalissimo” was one thing, but blessing the mass killing of party members, whose loyalty and stability were at the core of the policies of the ruling center-right faction of the Soviet establishment led by Brezhnev—that was a completely different story. The key principle of the ideology of the post-Stalin USSR was “don’t kill your own!” When Khrushchev, ousted and dishonored, was asked about his most important achievement, he replied, “They won’t shoot me.”

Thus, Semanov’s article in Young Guard was viewed as a violation of the sacred taboo. None of the “deputy bosses” could help the magazine. Publishing Demetyev’s article in Novy Mir had made Tvardovsky vulnerable, and the regime struck out at the liberal opposition. Now, Young Guard had put itself in the same situation—and it was time for the regime to strike the nationalist opposition. This time the regime counted all the mistakes of the right wing: “Chalmaevshchina,” Lovanov’s denouncing of the “educated masses,” and many more.

The Kommunist, a mouthpiece of the Communist Party, never lectured or reprimanded those at fault—it just announced a final verdict that could not be appealed. After Semanov’s article, The Kommunist wrote, “[Viktor] Chalmaev’s article ‘Inevitability’ drew attention primarily by its unprecedented extra-social approach to history, by mixing every fact of Russia’s past in an attempt to show all reactionary developments in a positive light, and even quoting such an arch-reactionary writer as Konstantin Leontyev.” Those words sounded like a death knell for Chalmaev. The verdict followed: “The authors who mostly publish their works in Young Guard should have listened to every rational and objective thing expressed by the critics of ‘Inevitability’ and in other articles, similar to those criticisms. Unfortunately, they haven’t. Moreover, some authors went further in their delusion, forgetting Lenin’s direct orders on the matters that they decided to judge.”

But The Kommunist’s public dressing-down of Young Guard led nowhere. Despite “Lenin’s direct orders,” neither liberals nor nationalists changed their views. Valery Kosolapov, who succeeded Tvardovsky as editor-in-chief of Novy Mir, was also a liberal, and after the resignation of Anatly Nikonov, Young Guard’s new editor-in-chief, Anatoly Ivanov, was also a nationalist. Such were the ritual and the logic of the Soviet centrist regime: radical representatives of both ideological wings of the opposition were shown their place. So they’d be more careful in the future.