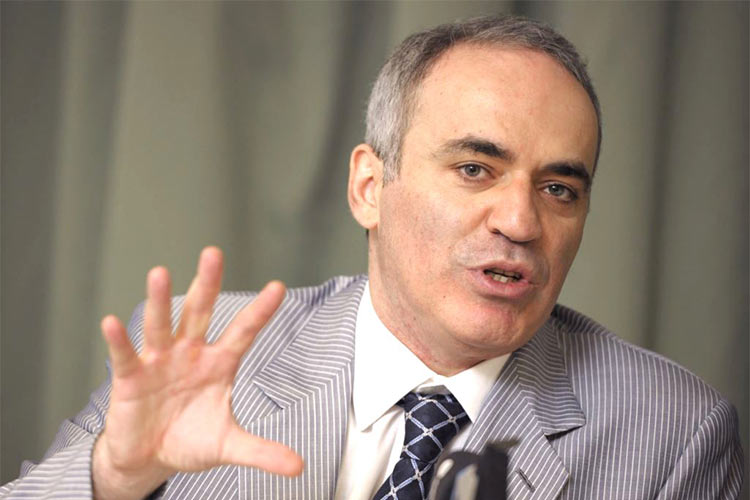

The Institute of Modern Russia continues its series of interviews with Russian and Western experts about the situation in Russia, its relations with the West, and the future of its political system. Journalist Leonid Martynyuk spoke with one of the leaders of the Russian opposition, chairman of the Human Rights Foundation Garry Kasparov, about the logic and features of the development of Putin’s dictatorship, his foreign policy escapades, and the conditions that could cause the fall of his regime.

According to Garry Kasparov, since Russian people don’t yet have the sense of an apocalypse, the chief task of the Russian opposition is to explain that under this regime no changes for the better are possible and that it’s a road to nowhere, a road into an abyss. Photo: Reuters.

Leonid Martynyuk: Some people think that following Boris Nemtsov’s murder Russia transitioned into a new sociopolitical condition. Do you agree with this opinion?

Garry Kasparov: Even earthshaking events, like the killing of a person of Boris Nemtsov’s stature, don’t change the situation so much as they reveal what is already taking place. The very fact that the authorities practically sanctioned this killing shows us the chasm that has opened in front of us.

This would have been impossible to imagine several years ago. The quotation from the German pastor Martin Niemöller has become a cliché, that when they arrested the communists, the labor union activists, and the Jews, he didn’t protest, because he was not one of them, but when they came for him, nobody was left to raise their voice in his defense. The growth of a dictatorship doesn’t occur overnight—it occurs gradually. And at some point it turns out that it’s possible to shoot dead the most prominent opposition figure in front of the Kremlin and to have nothing happen. And nothing does happen.

The authorities feel so brazen that they can openly sabotage the investigation. The most that can be expected is that they will imprison the perpetrators, and maybe not even the actual ones.

L.M.: How do you evaluate the current political climate?

G.K.: Today Russia finds itself in a situation where a boss lives only by loyalty to his higher-up boss. Loyalty has in fact replaced the law. It’s like in the Mafia: the word of the don is law. We see this in everyday life too. Recall the incident involving the Cossack activist Vladimir Melikhov. At the border they took away his foreign passport and an hour later gave it back, but with a page torn out, making the passport invalid. This mundane story shows that today’s Putinist boss will commit a crime without blinking.

This incident shows the extent of the total degeneration of the Russian regime—violating the law for the sake of momentary political expediency has become the norm. That is yet another confirmation of the fact that Russia today is a personal dictatorship in which a fascist ideology is followed everywhere. Russia has not yet become an absolute totalitarian state with mass repression. But in the context of the twenty-first century, we are in a situation where to hope for some kind of positive evolution of the regime is totally senseless.

L.M.: In May Putin signed the law about undesirable foreign organizations in Russia. Two days later a Duma deputy proposed closing down a number of leading NGOs, including Human Rights Watch and Memorial. Is Russia evolving along the lines of North Korea?

G.K.: The laws of physics also work in the political setting: motion on an inclined surface always picks up speed. And here we have to take into account historical experience. From Soviet Russian experience we know that there are internal laws that govern the development of dictatorships. It is quite obvious that [in Russia now] a qualitative change in the managerial apparatus is underway. During the building of the Soviet Union there was still a need for former White [movement] officers and bourgeois specialists, and the managerial system generally required people who had some vision of their own. But gradually that all changed, because instead of professional qualifications the personnel were required to show only absolute loyalty to the system and to the leader. And today, in Putin’s Russia, totally thuggish, senseless, malicious, and uneducated people are coming to the fore. This is the law of natural selection in degenerating systems. Soon it will turn out that even these people are too intellectual, and they will be replaced by absolute madmen. This is all related to the machinery of power, and specifically to Putin and his inner circle, because Putin’s power is absolute and is objectively comparable to that which Stalin had.

L.M.: What differences do you see between the Soviet dictatorship and Putin’s?

G.K.: Both the Stalinist dictatorship and Hitler’s regime ultimately tried to shape a vision of the future. Of course, it was a monstrous vision: in the Third Reich, domination by the Aryan race, and for Stalin, the victory of communism on a world scale. They tried to engage people with some kind of idea of the future, and this idea was held out as a positive one. It’s clear that it was bloody and paved with crimes, but it was wrapped in positive packaging. The uniqueness of Putin’s dictatorship lies in the fact that it doesn’t offer even a criminal positive vision of the future.

L.M.: And what about the Russian world?

G.K.: The Russian world has evaporated. If we look at the propaganda, we see a cult of death. The cult of death is gaining momentum, and at some point the insanity of the propaganda will swallow up the regime itself. There is no doubt that at the end of the war Hitler would have used the atom bomb without hesitation. Gradually the insanity of the dictator begins to infect those around him, and then there is no one to stop him. Hitler could have been stopped in 1936–38, but in 1939–40 it was already too late. Russia today finds itself in the situation in which Putin’s inevitable doom (because even now he can’t have a life outside the Kremlin) is beginning to afflict his retinue and spread through the entire machinery of government.

They preach the cult of death to us—"We are surrounded by enemies." Even the USSR had allies, and that was something to be proud of. It was a peculiar pride, but there were courses set for the future, and there was a plan. There is no Putin plan. All there is is a concentrated blast of hatred, [the belief] that everyone is an enemy. Only such friends as North Korea and Syria are left—the most thuggish dictatorships, which are not even on the periphery, but on the ash heap, of history.

L.M.: You say that Putin has no real allies. But Russian propaganda now actively promotes the idea that China is an ally of Russia and that they will resist the imperialist ambitions of the United States together.

G.K.: That brings to mind the old Montenegrin joke: “We aren’t afraid of German planes, because together with the Russians, we are 200 million” [Ed.—the original joke rhymes]. Together with the Chinese, we are 1.5 billion, but there are nine times more Chinese than Russians. But that’s not the most important thing. Nuclear weapons aside, the powers of the two countries are not at all comparable. China is a country that has a plan looking ahead many decades, if not centuries. And China looks at Russia as a territory to be swallowed up in the future. You don’t have to be a great geopolitical strategist to understand that China considers significant parts of Russia to be under temporary occupation: the Far East and Eastern Siberia.

Approximately half of Russia should become part of Greater China in the opinion of Chinese geopolitical strategists. And this process is very successfully under way—Chinese are settling on Russian lands. We don’t yet know the exact numbers, although even official statistics, which minimize by multiples the real number of Chinese, are alarming. It is clear that the current conflict between Russia and the West is beneficial for China. Russia signs lopsided agreements that are purely for the purpose of making China smile encouragingly. Strategically, [these agreements] ensure the Sinification of half of Russia’s territory.

L.M.: And doesn’t Putin see these threats? Does he have no choice? Or does he think that these threats will only materialize after his time?

G.K.: That is an important philosophical question, the answer to which must be sought in historical analogies. The fortunate dictator remains in power for many years precisely because he is concerned with his survival. He can’t permit himself to think strategically; his task is to survive today and then see about tomorrow. As soon as he begins thinking strategically, he is doomed, because he lives only by improvising the whole time, supposing that all around there are, if not enemies, then at least potential enemies. The Putin regime’s current Eastern policy is governed by the law of survival. From Putin’s point of view, the potential benefits of the sale of Russian territory, riches, and natural resources is endless—enough to last through his lifetime. And what comes after that for Russia has never been his concern and never will be.

Today, in Putin’s Russia, totally thuggish, senseless, malicious, and uneducated people are coming to the fore. This is the law of natural selection in degenerating systems. Soon it will turn out that even these people are too intellectual, and they will be replaced by absolute madmen.

L.M.: There are two points of view about Putin’s military strategy. The first is that Putin unleashed a military conflict in the Donbass so that the world would forget about the annexation of Crimea. The second is that Putin needs all of southeast Ukraine, and maybe all of Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and the Baltic countries. What’s your opinion?

G.K.: From the point of view of the dictator’s philosophy—"Take it all." But it is patently obvious that it can’t all be taken. A plan is being developed [by Putin and in the Kremlin] that defines the maximum that can be taken and includes the idea of the revival of the Soviet Union in some form. But it may not be attainable, and therefore interim plans have also been made. The crucial thing for Putin always was and still is to liquidate or substantially limit Ukrainian sovereignty. An independent Ukraine that chooses Europe is unacceptable for Putin as an apologist for the rebuilding of the Soviet empire. It is another matter that his plans contained a strategic miscalculation. Obviously Putin planned a lightning annexation of Crimea in advance, because, given typical Russian chaos, to carry out such a quick and successful operation in only two weeks would have been impossible.

This means it was planned well ahead of time. We can surmise that this operation to dismember Ukraine could have been prepared for 2015 in anticipation of the presidential election, and that upon the altogether likely defeat of Yanukovich, the Crimea/Novorossiya plan would have been carried out. The Novorossiya project was put together in advance, and Putin very confidently said as early as April of last year that Novorossiya would stretch from Lugansk to Odessa. The appearance of corresponding maps on Russian television shows that it was hoped that the Donbass scenario of overthrowing the local authorities, creating hotbeds of civil war, and [fostering] the appearance of volunteers would spread throughout all of southeastern Ukraine. The fact that the ethnic Russian populations of the Kharkov, Dnepropetrovsk, and Odessa regions turned out not to be receptive to the Novorossiya plan was a shocking discovery for Putin.

L.M.: What are Putin’s current tactics concerning Ukraine?

G.K.: Putin currently continues to see Donbass as a cancerous tumor on the body of Ukraine. He hopes that he will succeed in somehow implanting this malignant growth into the tissue of the Ukrainian state and in influencing Ukraine, which he considers part of his imperial project. His most recent speech in St. Petersburg at the [19th St. Petersburg International] Economic Forum was rather symptomatic and threatening: Russians and Ukrainians are one ethnic group, [he said,] and “we are doomed to a common future.” In Putin’s mouth, this phrase is a new warning that the war in Ukraine is not yet over.

L.M.: In March of this year, speaking at a hearing of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, you stated that the global community must support Ukraine by supplying weapons to it. Can such a measure stop Putin?

G.K.: What was being discussed was modern anti-tank and light weaponry and electronic surveillance systems—in other words, not heavy weaponry.

Supplying such weaponry has a two-fold purpose: first, to strengthen the army itself and raise the price of aggression for Putin; and second, as psychological support for Ukraine, which is actually the front line bridgehead where Putin’s aggression against Europe is being repelled. [Ukraine] can hardly stop full-scale aggression if Putin is ready for that, but it steeply increases the price of such aggression. The defeat of a dictatorship in war consists not only of defeat on the battlefield. The Soviet Union didn’t lose the war in Afghanistan in the military sense, but the political price—the “cargo 200,” society’s psychological fatigue, the foreign policy costs —all of these became an intolerable burden and in large measure led to the breakup of the Soviet Union.

L.M.: And when could the price of the war become intolerable for Russian society?

G.K.: Perhaps if the real figures for the losses in the Ukrainian war become known. It is therefore no accident that efforts have been made to keep these figures secret. And it is no accident that Boris Nemtsov, who wrote many incriminating reports about Putin—"Putin: What 10 Years of Putin Have Brought," “Putin. Corruption,” “Putin and Gazprom,” "Winter Olympics in the Subtropics“—was killed just when he began to write his report “Putin. War.” At that very moment the fatal shots were fired. [The real extent of Russian losses] is the most important government secret of all, and Putin understands that at some point it will become impossible to conceal these losses.

L.M.: Returning to the domestic Russian agenda: Does it make sense for the opposition to participate in the elections under conditions when the system is, as you said, not yet totalitarian, but already profoundly authoritarian?

G.K.: The only distinction between the system now and a totalitarian one is the absence of mass repression. But mass repression of the Stalinist type has become impossible now, because that would entail a purge of the elite itself. Putin’s Russia is built differently: in it, you can’t conduct a purge of the elite. For example, the criminal case against Serdyukov is falling apart, because it contradicts the very principle of the existence of the Putinist elite. This is to a great extent the principle of the Mafia: the only crime is to display disloyalty. This means that a transition to mass repression is impossible; Putin understands that that would amount to suicide. But the regime has mastered hitherto unseen tools—it has managed to create support points in various opposition groups. Putin has been in power for 15 years already, but the Russian political system was already fixed in place by the time Putin [came to power]. Today, if you look at the field of political opposition, you understand that the authorities permit only what is advantageous to them. If some kind of opposition game-playing is permitted in Kaluga, Kostroma, or Novosibirsk, it means that from the point of view of the authorities, that is advantageous. We will constantly witness the putting into play of topics that the authorities consider useful in order to reduce the intensity of societal friction.

L.M.: Can economic difficulties influence the stability of the regime? Industrial production in Russia in May of this year fell by 5.5% compared with May of last year. Real wages fell in April of 2015 by 13.2% compared to a year earlier. The number of poor people increased by 3 million in one year and is now 23 million. Sergey Guriev predicts turbulence.

G.K.: The worsening of living standards inevitably leads to increasing discontent and, quite possibly, to unrest among the population. On the other hand, the authorities are trying in every way to patch the holes with ideological propaganda. That is proving successful so far, because many people believe that the difficulties are temporary and that they are caused by the numerous enemies who won’t give our country any peace. The figures for the increase in the number of poor people will worry the authorities only if they lead to protests in the big population centers—especially in Moscow. All protests outside of Moscow have thus far been easily suppressed by the authorities. And the Moscow figures so far don’t outline an apocalyptic scenario for the authorities, because overall the situation in Moscow hasn’t reached the critical point, inasmuch as the Moscow middle class hasn’t realized that the situation under Putin is hopeless. This is the most important issue related not only to the Moscow middle class but also to the Russian elite. Any protests against the dictator are possible only in a situation in which a feeling of hopelessness has taken hold. There was a massive conspiracy against Hitler in July 1944 after the landing of the Allies in Normandy, when it became clear that there was no chance left and that the finishing off of Nazi Germany was just a matter of time. Today, in Russia, people don’t yet have that sense of an impending apocalypse. They live in a virtual world and continue to hope that everything will somehow be resolved.

Therefore I believe that the chief task of the Russian opposition is to explain that under this regime no changes for the better are possible and that it’s a road to nowhere, a road into an abyss. This is what we need to do, and not to legitimize the system by participating one way or another in the spectacles that it organizes.