The question of why Russia has been unable overcome authoritarianism for many decades now remains a central point for discussion among Russia scholars and broader public. This book provides a historical overview of the issue from 1917 to present day, delving into the specifics of the Soviet and Russian leadership and the rules of succession.

The story of regime changes in the Soviet Russia reads like a thriller in itself. Depicted above is General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev (center) with his soon-to be successor Leonid Brezhnev (right) at Lenin’s Mausoleum, 1963. Photo: drugoi.livejournal.com

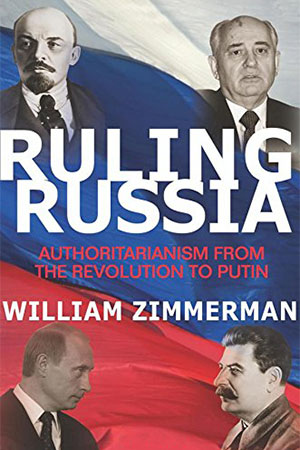

An evolving government is difficult to cleanly classify, even for experienced political scientists. In the case of Russia, these difficulties are exacerbated for Western theorists by existing preconceptions of “normal” Western democracy and a tendency to try to shoehorn Eastern governments into Western classifications. William Zimmerman, a research professor emeritus at the University of Michigan and a specialist in Russian politics, contributes to this discussion in his latest book, Ruling Russia: Authoritarianism from the Revolution to Putin.

Building upon the classifications historically applied to the forms of Russian government that have developed and disintegrated since 1917, the book takes note of the more subtle differences between government forms, evaluates the current government under Vladimir Putin’s leadership, and predicts that some form of authoritarianism will win out in Russia’s near future.

In order to evaluate the changing face of Russian leadership, Zimmerman begins by establishing four classifications of government under which he will attempt to fit the evolving Russian government from the October Revolution of 1917 to the present. He explains these categories as something akin to a spectrum between democracy and totalitarianism, with varying degrees of authoritarianism between the two extremes. His major contribution to this concept is his focus on the size of the “selectorate,” the group able to choose and remove leaders, as a defining characteristic that differentiates between various forms of authoritarianism. For example, the Soviet Union never deviated far from full authoritarianism, because even during the years of Gorbachev’s “glasnost,” leadership was effectively selected by a small group, and structures remained in place to ensure that the leadership would not be ejected. He continues his analysis through the fall of the Soviet Union and into the present, determining that much of Yeltsin’s regime fell under “competitive authoritarianism,” a state closer to democracy than totalitarianism. By the presidential election of 2008, however, the government under Putin had returned to full authoritarianism, because through media control, barriers to competition, and fraud, the power of choice was in the hands of very few.

While most of the book presents his perspective on history, Zimmerman is more interested in what the future holds. He predicts that the 2018 election will display the same barriers to fair competition as the 2008 election, but beyond 2024, he anticipates that domestic and international variables could lead to the creation of an opposition strong enough to move the country back toward competitive authoritarianism.

Zimmerman admits early in the book that the classifications on which he relies are not exact and that to attempt to follow them requires some “intellectual shoehorning.” This is a valid concern with his methodology, but he avoids oversimplification by allowing regimes to fall between one form and another and staying conscious of the fact that a single regime can at different times show qualities of multiple forms of government. He refuses to let one variable color his entire analysis at any point, but this hinders him at times from taking a clear stand. This is most apparent in his predictions for the future, where he avoids making a singular prediction and instead explains the variables that could lead Russia to one of several possibilities he outlines. Still, it is better that he opts for responsible caution rather than giving into the temptation to establish a strong position at the risk of oversight or inaccuracy. Zimmerman ensures that the complicated narrative he presents can be followed with relative ease, and his argument flows naturally and logically even while encompassing multiple themes. The book is written clearly and spruced up with interesting anecdotes and occasional humor, but it assumes the reader is familiar with the work of other analysts and with political science concepts, making it less accessible to casual observers of Russian politics. For those well-versed in political science and Russian history, however, this book offers a valuable perspective on authoritarianism in its detailed analysis of changing regimes and their effects on the governmental system as a whole.