In his latest comment on key developments impacting the Russian economy, Sergey Aleksashenko, nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and former deputy chairman of the Central Bank of Russia, analyzes the economic results for January and critiques the anti-crisis plan recently confirmed by the government.

Despite optimistic rhetorics by the Russian government, economists are skeptical about its anti-crisis plan. Photo: Dmitry Astakhov / TASS

The anti-crisis plan

The Russian government has finally adopted its anti-crisis plan; however, it raises more questions than hopes. To begin with, it took the government twice as long to develop the current plan as it did last year, when a similar plan was confirmed at the end of January.

Second, most of the measures incorporated into the plan to counter the crisis are open-ended in character: out of 48 expense items, 22 specify neither the amount nor the source of funding. All of those funds will still have to be “found” following the first six months of the budget implementation.

Third, it’s obvious that the government is in panic mode due to budget implementation issues and a lack of clarity regarding the amount of funds at its disposal. Although budget cuts are a decided matter, and even the defense ministry has confirmed 5-percent cuts to its current expenses, the government is disinclined to spend the released funds, lest the budget income turn out to be less than anticipated.

In a nutshell, it’s a plan of non-resistance to crisis—just let things continue as they are.

Difficult month

January is not a typical month for evaluating the state of the economy; therefore outlooks based on January data should be taken with a grain of salt. Still, one cannot help but notice the concern in the tone of communications issued by the Economy Ministry regarding the economic results of the first month of 2016. As most positions in the ministry are occupied by optimists (they have to be) who do not tend to dramatize the situation, we can assume that in reality the beginning of the year was less successful for the economy.

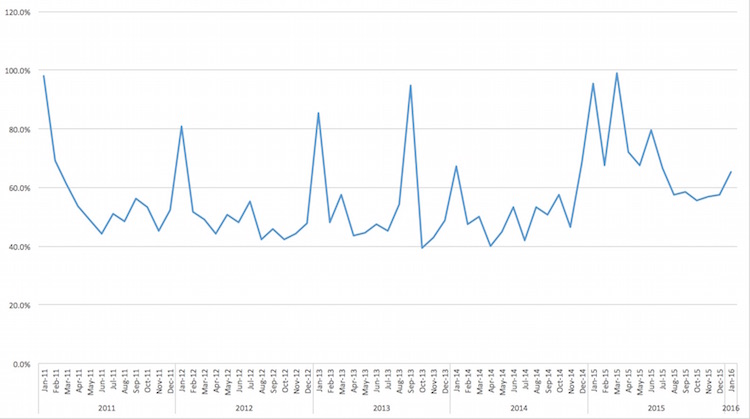

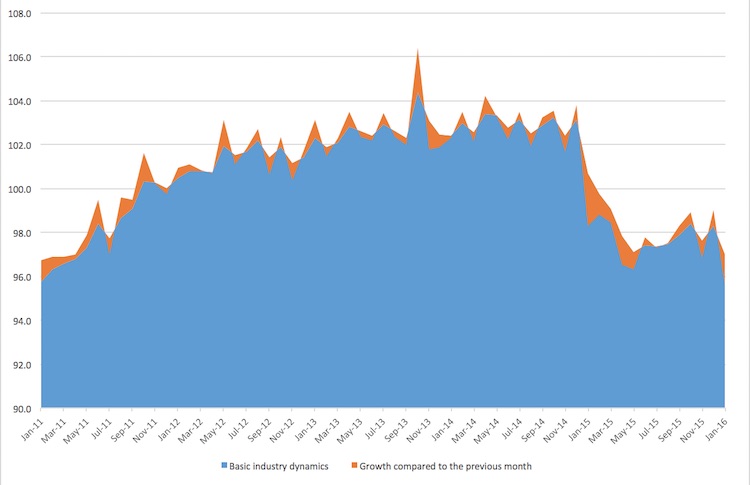

In early February, experts from the Higher School of Economics (HSE) Development Center arrived at rather pessimistic conclusions in their outlook for basic sectors dynamics (which correlate with GDP dynamics) in January. Some time ago, I compared their outlook with that produced by Vnesheconombank (VEB), highlighting their positive views on economic developments in Russia in the second half of 2015. I expect that following the January results, their optimism will fade. All of the economic “well-being” accumulated over the last six months has evaporated, as the economy slid downhill to a new low.

Chart 1. Basic industry dynamics in Russia, 2011–2016 (adjusted for seasonal factors)

Source: HSE Development Center

Chart 2. Basic industry dynamics in Russia, 2011–2016. Growth compared to the previous month (adjusted for seasonal factors).

Source: HSE Development Center

Mortgages

The Russian government’s inadequate outlook and sluggish decision-making has once again played “into the hands” of the crisis. Last summer, the government assumed that the crisis had already peaked, and thus refused to finance a rather efficient program for subsidizing mortgage interest rates. Funds allocated to this program were crossed out on the budget draft. But the government’s optimism was premature: once discussion on the new anti-crisis plan resumed, that program was again put on the table. But this year the program will be less efficient: rates for borrowers had increased; and a 15-percent reduction (compared to 2015) in the volume of mortgages was set as the target.

Corresponding changes to state budget law will not be introduced any time soon, though; therefore, funding for this program is currently out of the question. What this delay has already cost the economy is shown in the data: mortgage loans had dropped by 16.5 percent in January compared to the same period last year (both in terms of number and money value).

One more fact has emerged: the share of mortgages used for refinancing of the old ones is growing. This is good news for the public, who will have to payless, but from a macroeconomic viewpoint, we observe how misleading statistical data can be: the actual increase in mortgages is much lower than the Central bank claims.

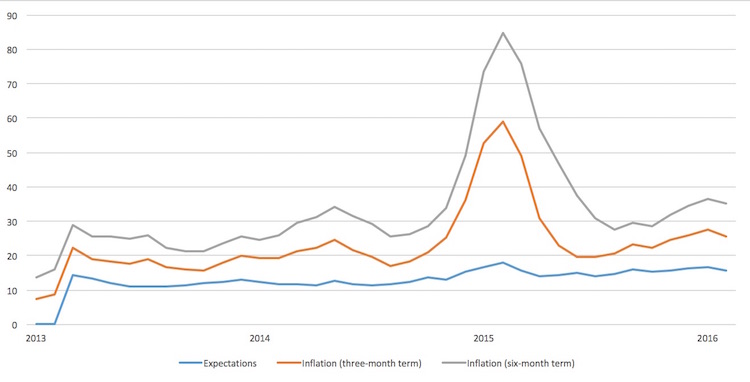

Inflation expectations

A recent poll conducted upon the request of the Bank of Russia showed only a slight decrease in inflation expectations among households.

Overall, these numbers confirm yet again that so far the Central bank has failed to suppress inflation expectations, which are the major source of continuing rapid price growth within the Russian economy.

Chart 3. Current inflation in Russia and inflation expectations among the general public (three- and six-month terms)

Source: Rosstat, Bank of Russia

No point in being afraid

Moody’s recently decided to put Russia’s sovereign rating on review for downgrade; however, there’s no point in overstressing the importance of this decision. For one thing, the decision was part of a lump categorization—many countries dependent on oil exports were put on similar review along with Russia. For another, the key limitation on Russia’s potential loaners is not the country’s rating or interest rates, but the financial sanctions against Russia. The informal character of these sanction was demonstrated last week, when U.S. banks backed away from purchasing Russia’s Eurobonds.